Viewing the Civil Rights Motion in coloration

The Black Lives Matter movement has sparked a debate about race and racism in the United States, and social media has been a major contributor to those conversations.

A popular claim being made on the internet is that civil rights photographers originally took their photos in color, but they have been switched to black and white to make them appear older when they appear in popular media and history books.

I was years old today when I found out that civil rights images were originally taken in color and were purposely shown to us in black and white to make us believe it was a long time ago. pic.twitter.com/v1JhI9YZb4

– wollega bby @ (@darawrXD) May 26, 2020

The post Office has nearly 60,000 retweets and 140,000 likes on Twitter and shows color photos of March 1963 in Washington, the Selma March 1965 and a demonstration in 1968 after the death of Martin Luther King Jr.

There is only one problem with this post – it is not true.

Although color photography was invented in the late 19th century, black and white photography dominated until the 1960s.

“Color just wasn’t as common as a medium at the time,” said Steve Harp, professor and co-area director of photography and media arts at DePaul University’s Art School. “It’s not that it was inaccessible – it just wasn’t used that much.”

Taking photos during the civil rights movement was very different from how photo sharing works today. Back then, photographers relied on wet film and some editors’ news judgment.

During the civil rights movement, cameras were bulky and expensive, and most of the photographers worked in newspapers and magazines. Black and white photography was the standard – it was faster, easier, and cheaper for both publications and photojournalists wanting to get their jobs done. If photographers wanted their photos to be published or seen by the public, they had to shoot in black and white.

Black and white photography was also seen as the “truer” form of documentation.

Photographer Bernard Kleina captured color images of the civil rights movement featured in Smithsonian Magazine. (Courtesy photo of Bernard Kleina)

“Black and white photographs tend to be that kind of signifier of a particular type of documentary photography … black and white seems to suggest that they are more truthful,” said Harp.

Many renowned photographers would even say that color photography was vulgar or of less artistic value than black and white.

Color images of the civil rights movement are rare. According to The New York TimesIn 1979, only 12 percent of newspapers printed some of their news pages in color.

What color photography of movement is there?

Exceptions are photographers such as Gordon Parks and Bernard Kleina, both of whom often take color photographs.

Parks was a pioneering black American photojournalist known for highlighting issues such as civil rights, poverty, and race in his 20th century job. He worked for Life Magazine, a publication known for its color images. Gordon worked to photograph his black subjects in color. This was a major challenge – the color film technology of the time became sensitive to white skin regardless of darker skin tones. According to Marcy Dinius, an English professor at DePaul, Parks used his background in fine art photography to figure out how to do it well.

In contrast to Parks, Bernard Kleina was an amateur photographer who almost accidentally began taking color photographs. The Chicago native and Roman Catholic priest was rushing to Selma at the time to document the 1965 protests and to produce his first “serious photos,” he said. It didn’t even occur to him to shoot in black and white.

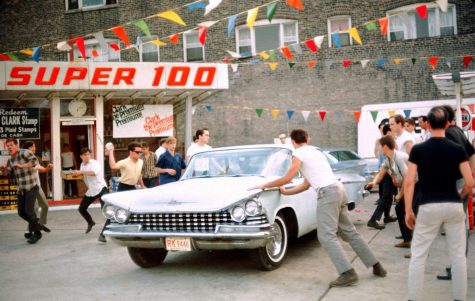

A mob attacks a car during the Chicago Freedom Movement of the 1960s. (Courtesy photo of Bernard Kleina)

A mob attacks a car during the Chicago Freedom Movement of the 1960s. (Courtesy photo of Bernard Kleina)

When King moved to Chicago, Kleina was there and ready to document the Chicago Freedom Movement. Kleina said widespread guilt for riots and criticism of King motivated him to photograph events.

“As well as taking pictures of Dr. King, I also took pictures of those who tried to block the march, throwing bottles and other things,” he said.

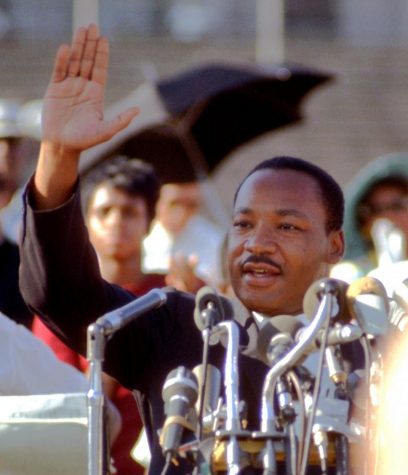

Kleina’s photographs have earned recognition as some of the only existing color photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. and have been exhibited in many museums, including the Smithsonian.

“For many people who have seen [my photos]It is the first time that she has seen Dr. See King in color, ”he said.

How do we see these photos now?

The American perspective on black and white photography has changed since the civil rights era. While black and white images were the norm for viewers in the 1960s, today’s viewers can view them as relics of a bygone era. For activists or even social media users like the one who posted the false claim, the black and white photography may not show the full picture.

Photography has never been so accessible. Almost everyone walks around with a high quality camera in their pocket and can take and distribute photos in just a few seconds. In contrast to the ordeal that developed a color photo during the civil rights movement, activists and protesters were able to share color photo and video content in real time during the nationwide protests against Black Lives Matter and other social justice movements last year.

Activists often use photography to counter the mainstream depictions of events in the media and have the ability to document and take photos themselves in color, Dinius emphasized. The use of social media and the power of photography to cover protests or speak out independently from government agencies or mainstream media is unprecedented, she said.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks to a crowd. (Courtesy photo of Bernard Kleina)

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks to a crowd. (Courtesy photo of Bernard Kleina)

Color photos of the civil rights movement can help viewers today make connections between the struggles for racial justice in the 1960s and today. However, some may wish to stick with the past. Kleina explained that despite his pioneering work with color photography, many people still prefer black and white images, perhaps because they have a more “historical feel” to them. He sees some resistance to his paintings and even has problems selling paintings to suppliers.

Seeing the civil rights movement both literally and figuratively in black and white can lead to an overly binary understanding of the movement, ignoring the many shades of gray (or steps in the middle) in between, according to Dinius.

“Color gives us a fuller spectrum and a more complex perspective,” she said. “It adds another dimension.”