John Simmons on photographing civil rights period

With its John Simmons camera, ASC has recorded important historical events such as the civil rights movement with portraits of Angela Davis and Shirley Chisholm and protests in Georgia against the Voting Rights Act. He’s also captured daily life, like a couple riding the bus and a little girl eating ice cream. His work extends from 1960s Chicago to today’s Los Angeles.

His work is featured in a new exhibition called Capturing Beauty: The Artwork and Photography by John Simmons. It is now on view at the CASA 0101 Theater in Boyle Heights.

Shirley Chisholm, 1971. Photo by John Simmons.

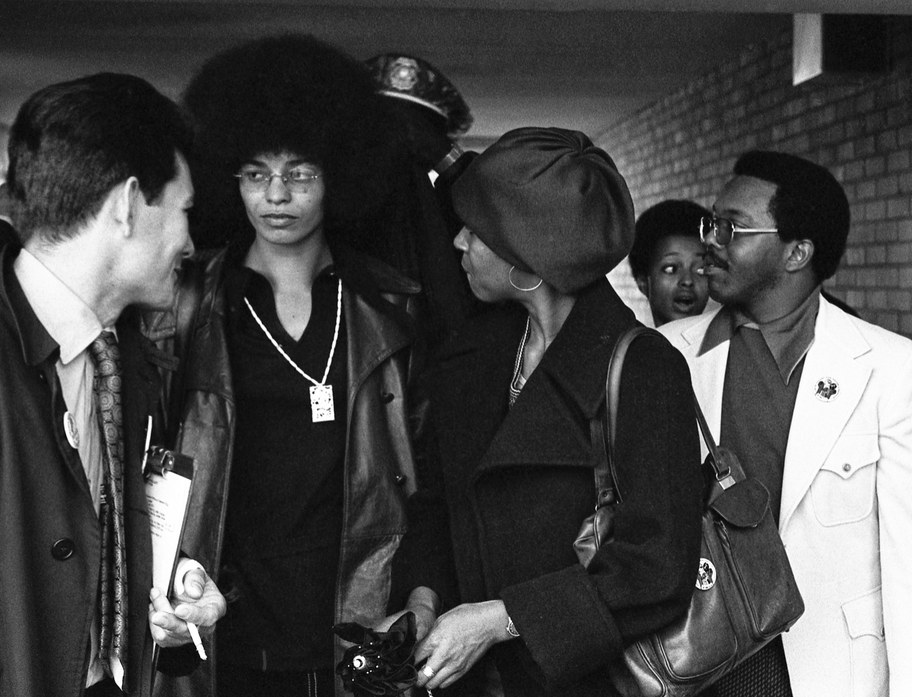

Angela Davis Nashville, TN 1972. Photo by John Simmons.

An unhoused Angeleno sleeping on the streets of Little Tokyo in 2017. Photo by John Simmons.

Simmons speaks to KCRW about his decades of work and how he keeps taking photos throughout a pandemic across Los Angeles.

KCRW: What made you choose photography?

John Simmons: “I was born in 1950. The 1960s were a pretty hip time in Chicago. The era of civil rights was hot. Jazz was there. A very passionate, cultural thing happened. There were hippies, there was a Vietnam War protest.

And when I was growing up, I wanted to identify with something. And as a kid, I was involved in art all my life and was drawn to that type of expression. I wanted to find my way, I wanted to be a musician, I wanted to be a poet. I wanted to be all of these things.

And a friend of mine, his older brother, was a photographer. His family owned The Chicago Defender, the oldest black newspaper in the country. Bobby Sengstacke was a very well known photographer. … And as a teenager, I always thought Bobby was one of the hottest cats I knew. He had cameras all over his shoulder and was working on jazz in a dark room. His brother and I have always admired him.

One day he let me borrow his camera at the Negro Publishers Convention. It was 1965 in New York and I was walking across the room to take pictures and he saw the photos and said, “Oh my god, you have one eye.”

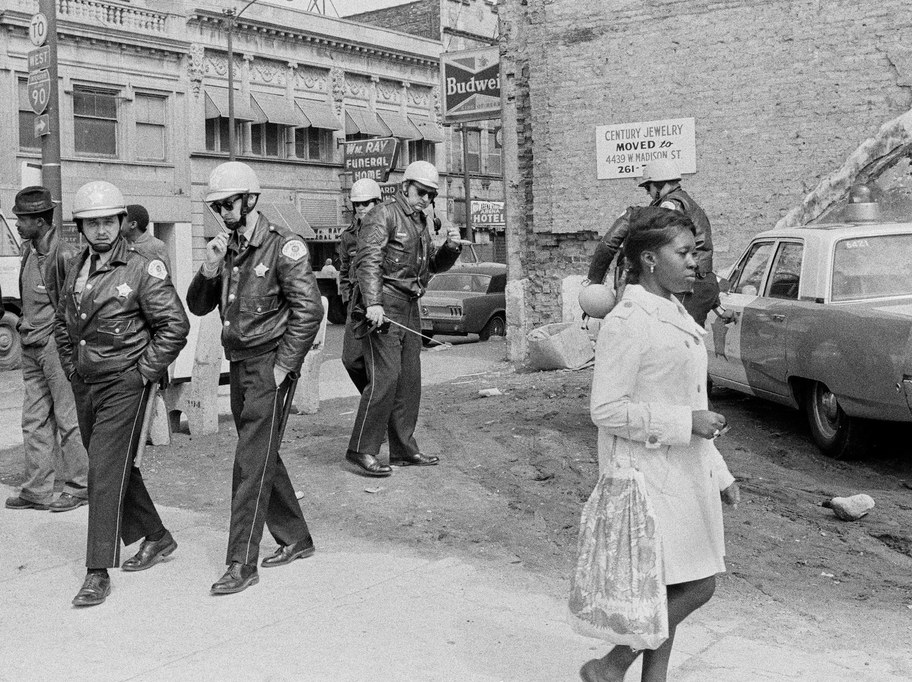

Cops and Girl, Chicago 1968. Photo courtesy John Simmons.

And I fell in love that day and looked through the camera. It was something I could do and it felt natural to me. And finally I started working for the newspaper. When I was 16, I took photos for her. Finally, I went to the University of Southern California to study cinematography.

And today I work as a cameraman and carry my camera every day like I always did. “

John Simmons says photography was a matter of course for him. Photo by Anaith Indjeian.

What were you looking for when you look back on your pictures of the civil rights movement?

“Every time I press the shutter button and take a picture, it’s a collection of everything I’ve ever done and who I am right now.

When I look back at these photos, that’s another cat taking these pictures and luckily there is a continuum. I can see the consistency of the visualization through the different periods.

But when I think back on those photos I think of how lucky I was to be in these places and to work for a newspaper that sent me assignments and to be able to get that scholarship at Fisk University at a time in that the culture was so rich and rewarding.

People from all walks of life appeared at this university. And it was a community that was still largely segregated, just as Chicago was the most segregated place I’ve pretty much ever been in that time.

But you are in this community, you are isolated. It encompasses the community where people actually supported each other at the time and everyone was like an extended family. They weren’t afraid of a camera because there was no social media to attack anyone. As I walked the streets with my camera there was a different kind of courage that everyone shared and a different kind of relationship. “

Blackstone Rangers, Chicago 1968. Photo courtesy John Simmons.

Did you feel like your life was in danger while taking photos?

“I found it very dangerous. The only photo called Macon that shows a portrait of a man behind whom the police are standing is in Macon, Georgia. And there are two policemen in this setting. And behind the policeman is another man wearing a baseball helmet. And he’s an assistant truck driver. The truck drivers were represented to control the peaceful crowd.

Shortly after I took the photo of this man, a policeman, one of those policemen hit me on the back with a baton. I fell to the ground. And when I turned and looked at him, his face was six inches from my face. And he said to me, “Don’t let the sun go down on me.”

But I also photographed the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968, which was also dangerous. So yes, I was evicted from areas, I was escorted from areas by police. And that just went with the job.

During this time I felt it was necessary to tell the story. So there was a bit of adrenaline that went with that whole feeling too. And I was young so I was bulletproof.

Parade, Chicago 1967. Photo by John Simmons.

But not now, because during the protests for George Floyd at the height of the pandemic, I went out to take pictures. But I was very careful, not because of the police, but because of the virus. Every time I went out and took photos of these events, I got back in my car as soon as it got a little crowded. “

When you look at photos you took of the George Floyd protests last summer compared to pictures you took in Macon, Georgia in the 1960s, how do they differ? And how are they the same?

“They are the same because both situations speak of the need for change and the people are passionate. And not only that, but now is a different time. Because now pictures speak to the world.

I mean, you’re looking at the girl who shot George Floyd while he was dying. At that moment this girl reached everyone in the world. So there is a difference.

And as for my paintings, I’m drawn to these events for the same reasons. Because I am moved by the importance of the message. And the difference is that social media is an outlet now before it wasn’t. “

Man with a Gun, Chicago 1965. Photo by John Simmons.