French Editor Pays Tribute to Civil Rights Icon Angela Davis

Europe, headlines, human rights, North America, TerraViva United Nations

Human rights

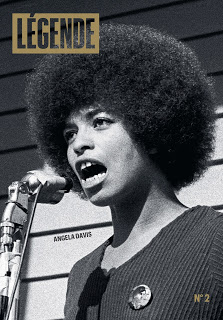

American civil rights icon Dr. Angela Davis. Photo credit: AD McKenzie.

– Well-known activist and intellectual Angela Davis turned 77 on January 26, marking more than five decades of her struggle against systemic racism and inequality.

January 2021 also marks fifty years since she appeared in a court in California to declare her innocence after a legendary manhunt and arrest. When sympathizers mobilized around the world to demand her freedom, she was finally acquitted of charges of “aggravated kidnapping and first-degree murder” in 1972 after 16 months in prison.

Since then, Davis has been a symbol of social justice and has never stopped speaking out. In 2020, her long history of activism saw another chapter when she joined protests in the United States – following the death of George Floyd and other police brutalities. Magazines like Vanity Fair have written articles about her and she has been featured in numerous other publications.

Last fall in Paris, her face flared from massive posters on newspaper kiosks in the city. The iconic image – big afro, serious eyes, open mouth in language – confronted pedestrians, drivers and bus passengers on their journey through the streets of the French capital.

The cover of Légende.

The posters announced a special issue of a new, independent magazine that had its second issue dedicated to Davis. The quarterly magazine called Légende is from Eric Fottorino, a former editor of the left-wing newspaper Le Monde. With a price of 20 euros per copy, the publication is not cheap; Still, many people bought the Davis edition. According to Fottorino, the magazine had several thousand subscribers by the end of the year.

The numbers may hint at the special place Davis occupies in the French folk fantasy, a place usually reserved for venerable rock stars. For example, when she spoke at a university in Nanterre, just outside Paris, in 2018, her mere presence received deafening applause.

Légende includes contributions from writers such as Danny Laferrière, Gisèle Pineau, and Alain Mabanckou, who ponder what Davis meant to them, and summarizes events from more than 50 years ago – detailing Davis’ membership of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s. and her involvement in the civil rights movement before and after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King in April 1968.

It also sums up the 1970 incident that made her known internationally: guns she bought were used by student Jonathan Jackson when he was taking over a courtroom to demand the release of black prisoners including his brother (George Jackson) , and went down the building with hostages, including the judge.

A subsequent shootout with police killed the perpetrator, two defendants he had rescued, and the judge, and Davis was arrested and charged after a major manhunt, despite not having been in the courtroom at the time of the hostage-taking.

These events are captured in bold photos and illustrations on the 90 pages of the magazine. For example, there is the reproduction of the “wanted” poster, warning the public that Davis should be viewed as “possibly armed and dangerous”; There are pictures of Davis in handcuffs who are later released. of her with family and friends, including writer Toni Morrison; her lectures at universities and public events.

The legend ends with a picture of Davis standing on the back of a convertible wearing a mask against Covid-19. Your right hand is raised in a fist. Nearby, a protester holds a sign that reads “NO JUSTICE NO PEACE”.

To find out more about the development of the magazine issue, SWAN interviewed publisher Eric Fottorino. Below is a short version of the interview that took place in Légende in Paris.

SWAN: Why did you choose Angela Davis for this issue?

Eric Fottorino: When we decided on this second edition of Légende, George Floyd had died in the United States and there were demonstrations in France regarding Adama Traoré, and since we wanted to introduce a woman, we decided on Angela Davis – about her To remind people of her work and to show that the struggle she waged for civil rights and feminism in the 1970s and later is still ongoing. We felt it was important to talk about Angela Davis’s past, be it in the US or in France. Very often we think that the present can only be explained by what is happening now, but it is important to know history.

SWAN: She spoke about the importance of international and French solidarity to her when she was arrested and imprisoned. Can you explain why French supporters took up your cause?

EF.: For the generation of the seventies she embodied a struggle, a dream for justice and exactly the opposite – she embodied a female victim of injustice, but one who would fight with all her strength, energy and intelligence. This was important for France because she had studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and therefore received a lot of support in intellectual circles, be it from Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet or Louis Aragon or from the Parti communiste français (PCF). It was also the subject of a powerful poem by Jacques Prévert. So she had intellectual and political support. There were marches too, and we have a photo of one of them where her sister (Fania) was marching with Aragon in the streets of Paris to protest for her freedom.

I think all these elements made her a popular figure in France, and the famous scream “Free Angela” heard in different countries around the world was picked up in France too. She also went on a tour when she was liberated – to say thank you, but also to make it clear that she was not giving up the fight. She appeared in the major literary programs of the time such as “Apostrophe” as well as in the studio of France Inter and the major public broadcasters. She was very present, and later a popular French singer, Pierre Perret, made a song about a person who became a victim of racism and you could see Angela Davis’ story in it, even if he didn’t specifically dedicate the song (Lily) to it her.

SWAN: How about the political newspapers of the time? What role did they play?

EF.: It had the support of socialist newspapers like L’Humanité, but it must be remembered that the Parti communiste was one of the strongest parties in the 1970s with around 25 percent of the vote. It was even stronger than the Socialist Party. So the support of people like Aragon (who was a member of the Parti communiste français) sent a great symbolic signal.

James Baldwin, who also supported her, was a well-known writer in France. He was not a popular writer, but in intellectual and literary circles, Baldwin was someone whose voice had weight because he had lived in Paris for some time and the fact that he wrote this open letter to his sister Angela (An open letter to mine Sister, Miss Angela Davis (1971), was remembered by the people (the translation by Samuel Légitimus is reproduced in the magazine).

SWAN: Did you try to talk to Angela Davis about the problem?

EF: We tried, but she was very busy and I think she was quite tired when we made the request. But there was no need for us to write about her life and the past. Of course, if she had been available we would have interviewed her, but we didn’t think it was essential. In a way, their actions and their lives speak for them.

SWAN: Some black French thinkers say that there is some kind of fascination and admiration for African Americans in France, including Angela Davis. How would you react to that?

EF: In France, fighters for social justice are not necessarily black, so there were no emblematic figures like in the USA with Angela Davis, Malcolm X or Martin Luther King and others.

It is true that blacks had a limited space in political life in France, and sometimes people outside of France say that there was no black minister or anyone celebrity, but they don’t know anything about Christiane Taubira or Kofi Yamgnane. So it is not true that such people did not exist. What is true is that there is no great emblematic political leader like Angela Davis here.

(Ed .: Fottorino has published another publication entitled “To be black in France” To be black in France.)