Brevard academics union seeks reinstatement of slain civil rights leaders

In 1946, their fight to better the lives of Black Americans in the Jim Crow South cost them their jobs. Six years later, it cost them their lives.

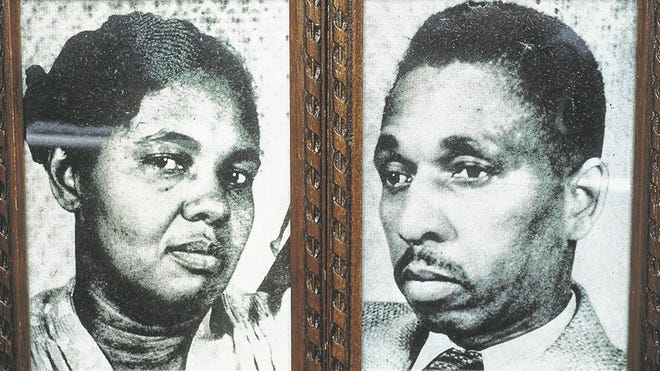

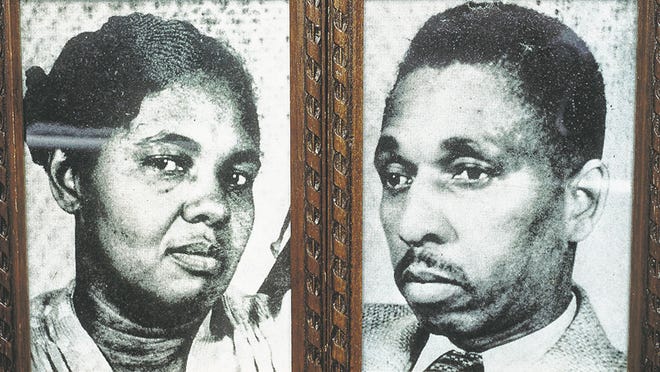

Today, Harry and Harriette Moore — a pair of Mims educators sometimes called the “first martyrs” of the modern civil rights movement — are still broadly unknown, even in the county they called home.

Nearly 70 years after their deaths, that may finally change.

The Brevard Federation of Teachers, with help from the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Cultural Complex, are working with Brevard Public Schools to incorporate teaching of the Moores into the school curriculum, ensuring their place among other civil rights heroes in the minds of Brevard students.

The union has also asked the the Brevard School Board to go a step further by posthumously reinstating Harry and Harriette Moore as teachers. It’s a symbolic gesture they say would help restore the Moores’ legacy and go some way toward erasing a black mark on the school district’s rocky racial past.

But correcting the past might not be simple. While Board members say they generally support the idea, just how far they can go to rehabilitate the Moores’ professional lives may depend on the murky details of an incident that happened almost 80 years ago. And if the school board admits it made a mistake eight decades ago, could there be legal consequences for it now?

Union President Anthony Colucci, who is spearheading the effort, said the idea to reinstate the Moores was spurred by the national atmosphere of heightened racial awareness following thecontroversial deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others at the hands of police.

Considering some of the inequities people of color experience in Brevard led naturally to the Moores, who lost their teaching positions after Harry Moore’s civil rights activism became too much for an all-white school board to bear.

The possibility of righting that wrong, Colucci said, would deepen an ongoing conversation surrounding racial injustice and perhaps restore some dignity to a pair of early civil rights leaders too often left out of the history books.

“To me, I can’t believe this hasn’t been done already,” he said. “There definitely needs to be more discussion about these things in Brevard County and correcting a major blemish with these great civil rights leaders is a great place to start.”

The ‘first civil rights martyrs’

The bomb went off about 10:20 p.m. Christmas night, 1951.

The explosion rent the foggy night air, booming out across the citrus groves of Mims and sending shattered pieces of the Moores’ home flying in all directions.

Amid the rubble, Harry T. Moore, 46, and his wife Harriette, 49 — Harry a long-time principal and Harriette a teacher in the north county “colored” schools, as they were then known — laid bleeding and broken. Harry Moore died on the way to the hospital, cradled in his mother’s arms. Nine days later, Harriette Moore followed.

The bomb, so carefully placed beneath the floor below the Moores’ bed, had done its job, ending the lives of two Black Americans who had dared to dream of equality in the segregated South.

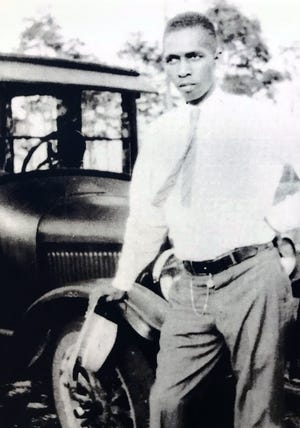

For decades before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the 1954 Supreme Court case that overturned segregation in schools and kicked off the modern civil rights movement, Harry Moore was fighting to bring that dream to life.

In 1934, he started the Brevard County chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and, over the next 17 years, would go on to aid or establish dozens of new chapters across the state.

In 1937, he helped file an ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit against the Brevard County School Board to equalize pay between Black and white teachers — the first of its kind in the Deep South — and in 1944 cofounded Florida’s Progressive Voters League, which went on to register nearly 100,000 new Black voters.

A few years before his death, Moore began to investigate lynchings and other cases of racial injustice, including the infamous 1949 Groveland case in which four young Black men were wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in Lake County.

Harry Moore’s efforts might not have been possible without the support of Harriette, who stood by her husband despite mounting racial and political tensions caused by his growing influence. She also shared, unflinchingly, the many prices Moore paid for his work.

All of this was in the face of often open hostility from white officials in Brevard and across the state, and from groups like the Ku Klux Klan, members of which were ultimately suspected of orchestrating the deadly Christmas bombing, though the case never went to trial.

In his book, Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore, America’s First Civil Rights Martyr, author and journalist Ben Green compared Moore’s prolific work favorably to that of better-known civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers.

“It seems evident that the work (Moore) was doing from 1934 to 1951 … was as courageous, as significant, as groundbreaking for that time as any of the later struggles of the civil rights movement,” Green wrote.

Colucci said Harry Moore has long been a model for his own work with the teachers union.

“Personally, Harry T. Moore has been an inspiration to me in the work I do as an activist in Brevard County,” Colucci said.

“When I was a social studies teacher in North Brevard, I was on the education committee at the Moore Cultural Complex, so I know the story fairly well with the Moores,” he said. “I always greatly admired his courage, intelligence and effort … to start correcting the wrongs in our society.”

Before their lives, their jobs

In 1946, six years before the bomb that killed them, another explosion rocked their personal lives: the Brevard County School Board failed to renew their teaching contracts. With the exceptions of Harriette Moore’s brief stint as a life insurance agent and various odd jobs to supplement their paltry incomes, it was the only career either had ever known.

In an interview with FLORIDA TODAY, Green said it was Harry Moore’s activism that led to their termination.

“Because of the political activism, the NAACP work, (Moore) was seen as a troublemaker,” Green, the biographer, said.

It began with the 1937 lawsuit against the School Board. The suit, which targeted the drastic disparity in pay between Black and white teachers, led to the immediate firing of Cocoa teacher John Gilbert, the only local educator brave enough to add his name to the filing papers.

Moore’s later work with the NAACP and especially the Progressive Voters League, which by 1946 was amassing a Black voting bloc powerful enough to threaten white politicians across the state, was the last straw.

The sudden news of losing their jobs turned the family upside down, Harry and Harriette’s daughter Evangeline Moore told Green during the research for his book.

“This was a horrific event in the family, … a total shock,” Green said. “It was one thing they fired Harry. He was visibly active, but that they fired Harriette too, that they were both out of work. … It was a very scary time.”

Retaliatory firings against Black teachers who challenged the status quo at the time were not uncommon, Green said.

Alongside more violent tactics like beatings and lynchings, such measures were used to keep Southern Blacks cowed and compliant, said William Gary, president of the Moore Cultural Complex.

“Many of the people who were registering to vote were afraid to do that because their jobs were dependent on what their white supervisors wanted them to do,” Gary said. “If you worked for Mr. John, and Mr. John knew you tried to vote, you very likely would lose your job.”

“That was part and parcel of the voter intimidation, voter suppression during the 50s, 60s, into the 70s,” he said.

Were the Moores fired?

Seven decades after their deaths, reinstating the Moores teaching contracts would be a purely symbolic gesture. But a symbolic gesture is exactly what’s needed right now, Colucci said, especially amid a year marked by yet another nationwide spate of high-profile African American deaths.

“Every time I read that Brevard Public Schools fired the Moores in 1946, there needs to be a sentence after that, that in 2020 the Brevard County School Board took ownership of that and made this right for the Moores, for the county and for the entire country.”

Ironically, just how wrong the school was could well affect how right they can afford to be.

According to School Board members Misty Belford and Matt Susin, School Board legal counsel has expressed reservations that reinstating the Moores could leave the board open to legal liability, perhaps in the form of a wrongful termination suit by the Moore family, Susin said.

In truth, the actual circumstances surrounding the end of their employment, which has received only brief attention from journalists and historians, is cloudy.

The usual account, advanced by the Moore Cultural Complex, news outlets like the Washington Post and the couple’s family and friends, is that the Moores were fired. But handwritten notes in their school district personnel files, on display in at the complex in Mims, raise the prospect thatthe Moores may actually have resigned.

This possibility is supported by some contemporary accounts from school board members and then-Superintendent Damon Hutzler, recorded in Federal Bureau of Investigation reports made just after the Moores’ deaths, and from Harriette’s mother, Annie Simms.

Hutzler also denied Moore’s activism had anything to do with the failure to renew their contracts, telling agents at the time that Harry Moore was “lazy in comparison with some of the other negro principals,” and that Hutzler had cause to reprimand Moore on several occasions, including once catching Moore sleeping in front of a class.

Hutzler, however, was the only school official interviewed during the initial investigation that spoke negatively of Moore’s performance. When the bombing case was reopened in 2004, investigators for then-State Attorney General Charlie Crist noted that Moore was overwhelmingly popular with his colleagues and students.

The fact that Hutzler may have lied to agents about his knowledge of Moore’s activism casts further doubt on his story. In a Jan. 5, 1952, interview he told FBI investigators he “never knew (Moore) was involved in the activities of the NAACP until the recent publicity resulting from his death.”

Green called Hutzler’s suggestion “too absurd to take seriously.”

“It’s just completely ludicrous that Hutzler was unaware of Moore’s activities. He was holding Emancipation Day celebrations. There were multiple things that he was very visible and noticeable in prior to 1946,” Green said.

Crist’s investigators agreed in a 2006 report, calling the superintendent’s testimony “highly suspect” and noting the chairman of the School Board at the time had reported Hutzler was “well aware of Moore’s political activities.”

Whether the Moores were fired or resigned after they learned their contracts were up, it was clear from testimony of School Board member John Nash that the board disapproved of Harry Moore’s activism, which ultimately cost them their jobs.

“Nash advised Moore that he … would not recommend (Moore) for reemployment as long as Moore was engaged in any political activity,” Crist’s investigators wrote about a confrontation between the two men shortly after the contracts were denied. “Nash explained that Moore was very active in the Progressive Voters League, and Nash was of the opinion that school teachers should not engage in politics.”

Their ultimate vindication

While the legal feasibility of a full reinstatement is up in the air, Belford and Susin both agree some action to recognize the Moores was long overdue.

“It’s an absolute tragedy that someone that was trying to have individuals inside our state vote was actually killed. … I’m full-force in favor of giving all rights back to the Moores,” said Susin, who wrote his senior college thesis on Harry Moore following a classroom visit by Ben Green in the late 1990s, just after the publication of his book.

“I think when we dance around the legalities of this and that, we forget what the true passion was,” Susin said.

At the least, Belford said, she would “without question” support adding the Moores to the school curriculum, along with other important civil rights history from the area.

Superintendent Mark Mullins said such an effort was already underway, following the union’s request: a team led by new Director of Equity and Diversity Danielle McKinnon is working with the union, the Moore Complex, and others to develop specific modules on the Moores for its 4th-grade curriculum and high school electives, Mullins said.

“That suggestion actually opened an opportunity for us to think further on how we might elevate the legacy of the Moores, and this history we have in our community for our kids as well as us as citizens of Brevard to connect with,” Mullins said. “That’s an opportunity I want to make sure we don’t miss.”

While Colucci said reinstating the Moores would assuage in some small way the taking of their jobs, a permanent place in the classroom curriculum could be their ultimate vindication.

“We need to correct the injustices of the past as best we can in order to focus on improving inequities in the future,” Colucci said.

“As we move forward in this country and we’re learning more and more about a number of injustices that were done to Black people,” Moore Cultural Complex President Bill Gary said, “now there is an opportunity to at least acknowledge that and make some effort to set the record straight.”

“It’s part of the reconciliation that we are all Americans, and that we have a dark chapter in the history of this country,” Gary said. “Not to place blame, but to reconcile feelings of disenfranchisement and bring about more feelings of inclusion.”

Contact Rogers at 321-242-3717 or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @EricRogersFT.