The State Finances for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023

New Hampshire’s new State Budget will fund State-supported services during a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The dynamic public health environment at the beginning of the budget period suggests that the health and economic well-being of Granite Staters, particularly those with the fewest resources, may be at considerable risk during the next two years. Significant federal supports for individuals, families, and institutions have had vital roles providing relief and supporting the early recovery, and will continue to be important as the pandemic risks are alleviated over time. Key services and operations supported by the State Budget will also be on the front lines of addressing both acute public health and financial security needs of New Hampshire residents.

The State Budget for this crucial budget biennium, from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023, provides additional funding in several key areas, including certain health and social services, long-term housing development support, additional public education aid targeted at communities with more low-income students, and physical infrastructure for mental health services. Funding to local schools will be boosted to offset declines in student enrollment made more acute by the pandemic, and more aid is directly shared with municipalities in aggregate. While increasing funding overall, the new State Budget requires unspecified reductions in funding at the Department of Health and Human Services and caps positions at that Department. The State Budget also establishes a voluntary family medical leave insurance program.

The new State Budget reduces available resources to fund ongoing and future services. The State Budget, combined with separately-passed legislation altering the State’s Business Profits Tax, is estimated to result in approximately a quarter billion fewer dollars in revenue than would have been collected without the changes. Long-term changes to key tax revenue sources, including the Business Profits Tax and the Interest and Dividends Tax, will disproportionately benefit the larger entities and high-income individuals, respectively, who pay a significant proportion of these taxes. The new State Budget also does not extend one-time education aid targeted at communities with smaller property tax bases, and directs additional resources to municipalities with relatively large property wealth compared to their student populations. Policy language in the State Budget also increases the likelihood that significant amounts of State funds previously dedicated to local public education will be deployed for private or home-school education.

Significant statutory language not related to State fiscal policy is included in the State Budget. Sections of this language restrict certain speech in public programs related to systemic racism and sexism, while other components limit access to abortion services after 23 weeks of pregnancy. Language in the State Budget also expands the Legislature’s role when the Governor declares a State of Emergency.

This Issue Brief examines key components of the State Budget for the next two fiscal years, approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor, and provides comparisons of funding levels for services to the State Budget for the prior biennium, which ended June 30, 2021. This Issue Brief also outlines key policy initiatives, changes in tax law, funds shifted to outside of the State Budget, and resources dedicated for specific purposes within the new State Budget.[1]

The Topline Changes

The new State Budget for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2022 and SFY 2023 increases appropriations relative to the prior State Budget. The appropriations made by the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget bills, approximately $13.6 billion, grow about $366 million (2.8 percent) from the $13.2 billion in appropriations made by the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget bills. Those figures are not adjusted for inflation and include all appropriations in the Operating Budget Bill (typically House Bill 1) and the Trailer Bill (typically House Bill 2) for the two SFYs of each budget as well as appropriations of surplus from the prior year made by the Trailer Bill, as those are expenditures authorized by the two bills typically included in the State Budget. For the purposes of comparing the two budgets, the new budget’s figures also include about $188.2 million that was appropriated but moved entirely off budget and approximately $30 million in federal funds that are likely to be accepted and incorporated into the State Budget later, as the comparable appropriations were included in the previous State Budget.

Without these adjustments and focusing on the primary section of the Operating Budget Bill, total appropriations increased $132.7 million (1.0 percent) between the previous and new budgets, and General Fund appropriations increased by $16.4 million (0.5 percent) while Education Trust Fund appropriations decreased by $12.9 million (0.6 percent). However, significant appropriations were enacted outside of the primary section of the Operating Budget Bill, including both increases and decreases.[2]

Expenditure by Category of Government Services

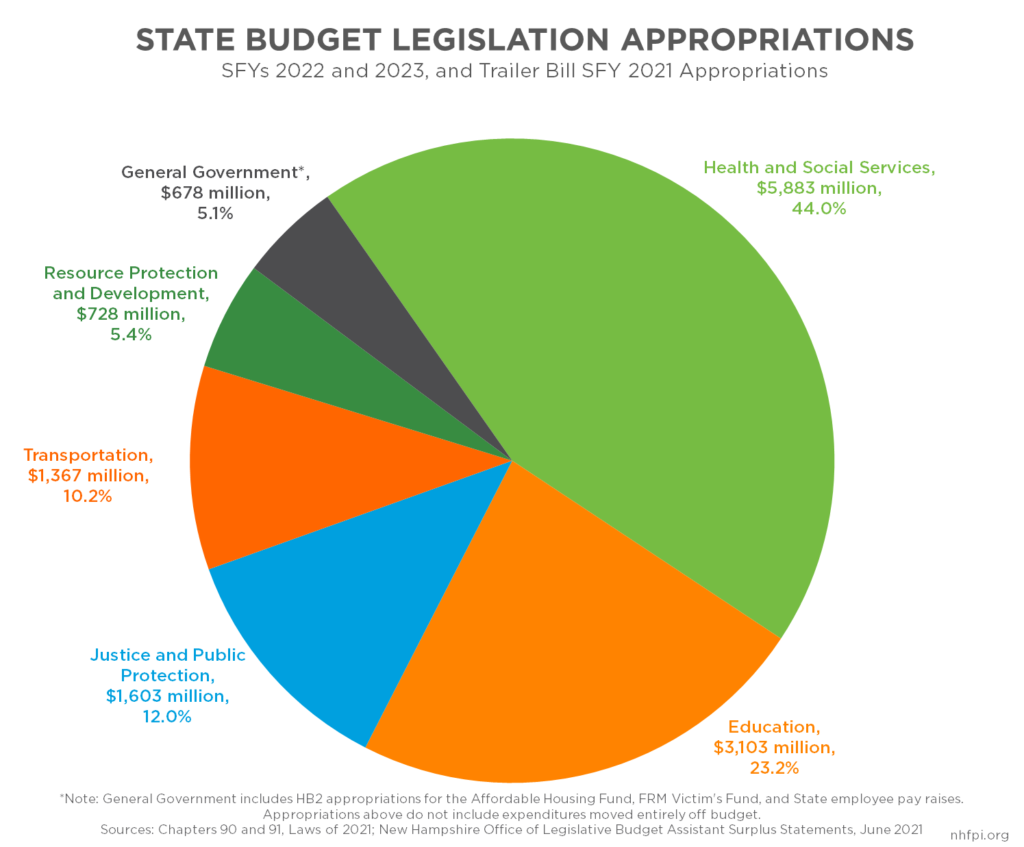

All State Budget expenditures are allocated to one of six categories based on the service area of each agency. These six categories are designed to cover all areas of State government operations, and include General Government, Justice and Public Protection, Resource Protection and Development, Transportation, Health and Social Services, and Education.

As with all other recent State Budgets, the plurality of appropriations among these six categories goes to the Health and Social Services category. This category, which with nearly $5.9 billion in funds accounts for about 44.0 percent of all appropriations from the State Budget bills, is almost entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; the category also includes the New Hampshire Veterans Home, which has a much smaller budget. Both agencies have been directly addressing the COVID-19 pandemic’s challenges as a part of providing their services. A significant amount of federal funding, particularly through Medicaid, flows through this category.

The next largest category, Education, includes State-sourced funding for local public education through the Adequate Education Grants provided to local governments on a per pupil basis. These Grants and other associated aid to local school districts, including school building aid and tuition aid to public charter schools, accounted for approximately $1.98 billion (63.9 percent) of the $3.10 billion appropriated to the Education category. The remaining appropriations included funding operations at the New Hampshire Department of Education, State support for New Hampshire’s University System and Community College System, and appropriations for the Lottery Commission (which generates revenue for the Education Trust Fund) and the Police Standards and Training Council.

The Health and Social Services category and the Education category combined together account for approximately two out of every three dollars appropriated in this State Budget, while the other four categories comprise the remaining appropriations. Justice and Public Protection, which includes a wide variety of agencies such as the Departments of Safety, Corrections, Justice, Insurance, Banking, and Labor as well as the Judicial Branch and the Liquor Commission, was appropriated $1.6 billion over the biennium. The category of Transportation, which includes only the Department of Transportation, received about 10.2 percent of the appropriations made by the State Budget bills, or nearly $1.4 billion during the biennium. Resource Protection and Development, which includes the Departments of Business and Economic Affairs, Fish and Game, Natural and Cultural Resources, and Environmental Services, accounted for about $727.5 million (5.4 percent) in appropriations. General Government was the smallest category, with about $678.2 million (5.1 percent) of the total appropriations for a wide variety of agencies, such as the Departments of Administrative Services, Treasury, Revenue Administration, and Information Technology, and including the Secretary of State as well as the entire Legislative Branch.

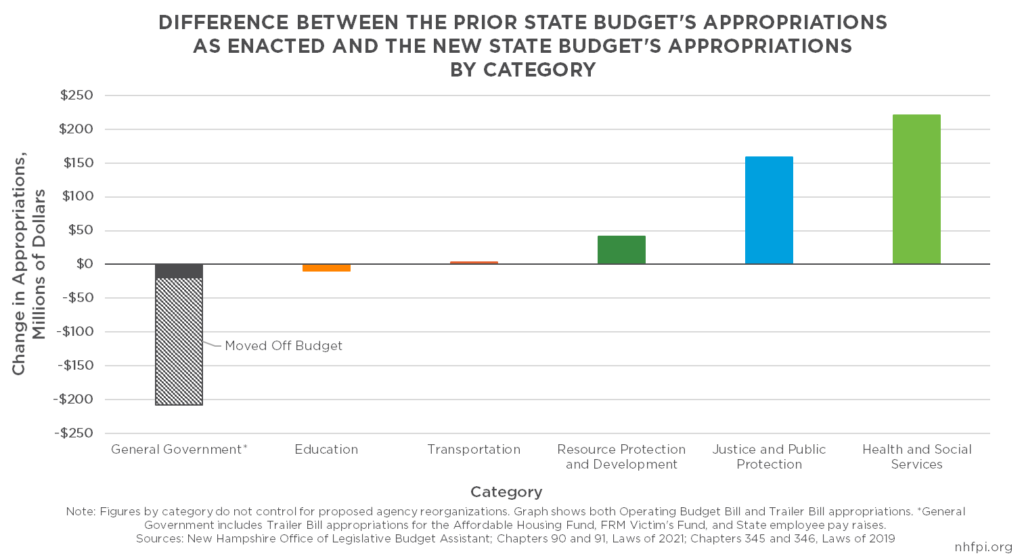

Although appropriations increased in aggregate, not all categories received increases in funding in the new State Budget. The largest dollar increase came in the Health and Social Services category, with an increase of $220.4 million (3.9 percent) in aggregate appropriations relative to the prior budget. While this increase was the largest, it was significantly less than the approximately $339.7 million increase proposed by the Governor relative to the prior State Budget at the beginning of the Legislature’s budget process.

Justice and Public Protection saw the second-largest dollar increase, at $158.6 million, and the largest percentage increase over the prior budget, with an 11.0 percent boost in the new budget. Resource Protection and Development followed with the third-largest dollar increase and the second-largest percentage increase, at $41.9 million and 6.1 percent, respectively.

Both the Transportation and Education categories saw little overall funding change, although many funding amounts and mechanisms changed within the Education category. Transportation saw a slight funding increase of $3.8 million (0.3 percent), while Education saw a larger change, a decline of $10.0 million (0.3 percent), compared to the prior State Budget.

General Government saw the most significant decline, a $208.0 million (23.5 percent) reduction, relative to the prior budget. Most of this decline, however, was due to the $188.2 million shifted off budget by policymakers in an expenditure line that was included in the prior State Budget. With this $188.2 million included in the appropriations, the decline was $19.8 million (2.2 percent).

Changes By State Agency

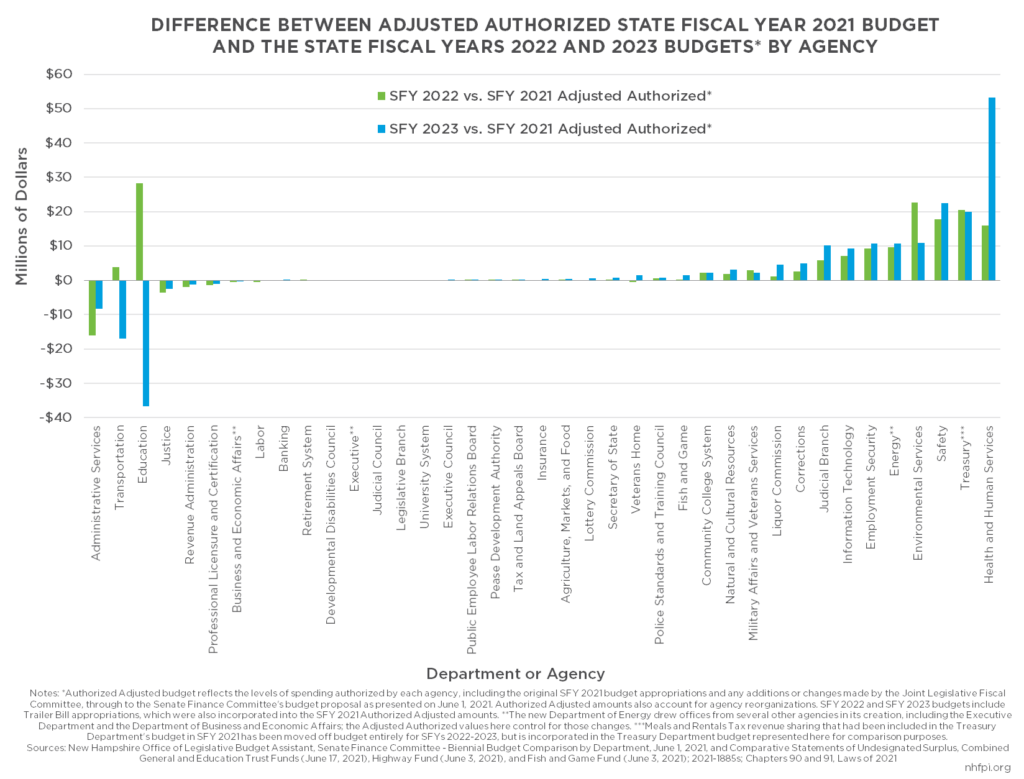

Relative to their budgets for SFY 2021, some State agencies were appropriated substantially different amounts of resources in SFY 2022, and a few will have significant changes in the amount of resources between SFY 2022, the first year of the new State Budget, and SFY 2023, the second year. These changes reflect the appropriations made in both the Operating Budget Bill (House Bill 1) and the Trailer Bill (House Bill 2) as well as allocations of revenue surplus from SFY 2021. The changes are in comparison to the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amounts for State agency budgets as of June 1, 2021, with adjustments made for the reorganization of departments, including the new Department of Energy, to provide direct comparisons. Adjusted Authorized budget figures also account for any additional funds or federal grants allocated to agencies since the prior budget’s enactment.

In this analysis, Trailer Bill appropriations of SFY 2021 surplus not specifically allocated to either SFY 2022 or SFY 2023 were allocated to SFY 2022, including appropriations made for physical infrastructure or specific projects. In many cases, agencies may also spend these dollars in SFY 2023, but the dollars are immediately available for expenditure starting with the enactment of the State Budget, effectively meaning all funds are available in SFY 2022.

In the SFY 2022 budget, 23 of 39 agencies (59.0 percent) separately identified at the department-level had funding increases from the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amounts, while 14 (35.9 percent) had decreases in funding and two (5.1 percent) had no change. The two agencies with no change were the Legislative Branch and the University System of New Hampshire. These two agencies also had no change between SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amounts and SFY 2023. In SFY 2023, 25 agencies (64.1 percent) had funding increases relative to SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amounts; relative to the prior year, the Departments of Transportation and Education, as well as the New Hampshire Retirement System, saw funding decreases that dropped them below the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted levels using this measurement methodology, while the Banking and Insurance Departments, the Lottery Commission, the Executive Council, and the Veterans Home have funding increases that will bring them from below to above SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted levels in SFY 2023.

The largest changes in dollars appropriated come in the form of increases at the Departments of Health and Human Services, Treasury, Safety, Environmental Services, Energy, and Employment Security, as well as decreases at the Departments of Administrative Services, Transportation, and Education, with both Transportation’s and Education’s funding levels changing significantly during the biennium.

The Department of Health and Human Services figures include both back-of-budget reductions eliminating positions and additional funding for a new secure psychiatric facility. The Treasury Department increase reflects additional aid to municipalities, moved off budget in the new State Budget but included here for comparison purposes. The increases at the Department of Safety are primarily driven by added Federal Funds due to COVID-19 disaster-related expenditures, increases in salaries and benefits, additional employee positions, and added aid for counties and local governments to support the Substance Abuse Enforcement Program.[3] The Department of Environmental Services will draw more loans and grants from the Drinking Water and Groundwater Trust Fund for use by the Waste Management Division, including to address contaminants.[4] The increase at the Department of Energy, a new department, reflects an aggregate funding increase at the component parts that contributed to the Department of Energy, including the Public Utilities Commission and the energy policy portion of the former Office of Strategic Initiatives, as well as new funding for the new Commissioner of Energy’s office.[5] The increase at the Department of Employment Security was primarily driven by an increase in Federal Funds for program services.

The decrease in funding for the Department of Administrative Services is attributable to an expected one-time decrease in cost for State retiree health benefits due to shifting plans and leveraging federal funds.[6] The Department of Transportation did not have a decrease in funding relative to the prior State Budget as passed, but has a smaller budget relative to the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amount in SFY 2022, offset by an infusion of one-time funds, and SFY 2023. The Department of Education also sees an infusion of one-time State aid to local school districts in SFY 2022, but sees a reduction relative to both SFYs 2022 and 2021 in SFY 2023 due to the expiration of one-time aid to school districts in the prior budget and in the first year of the new State Budget.

Health and Human Services

With the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacting the health and economic well-being of many Granite Staters, increased needs for health and economic supports during the budget biennium adds to the importance of this key area of State-supported services. The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) is the largest State agency and administers several critical programs, including Medicaid, the Food Stamp Program, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, all of which include significant amounts of federal funding support. Medicaid, which provided health coverage for more than 222,000 Granite Staters at the end of June 2021, totaled approximately $2.1 billion in expenditures in SFY 2020, with more than half of those expenditures funded by the federal government.[7]

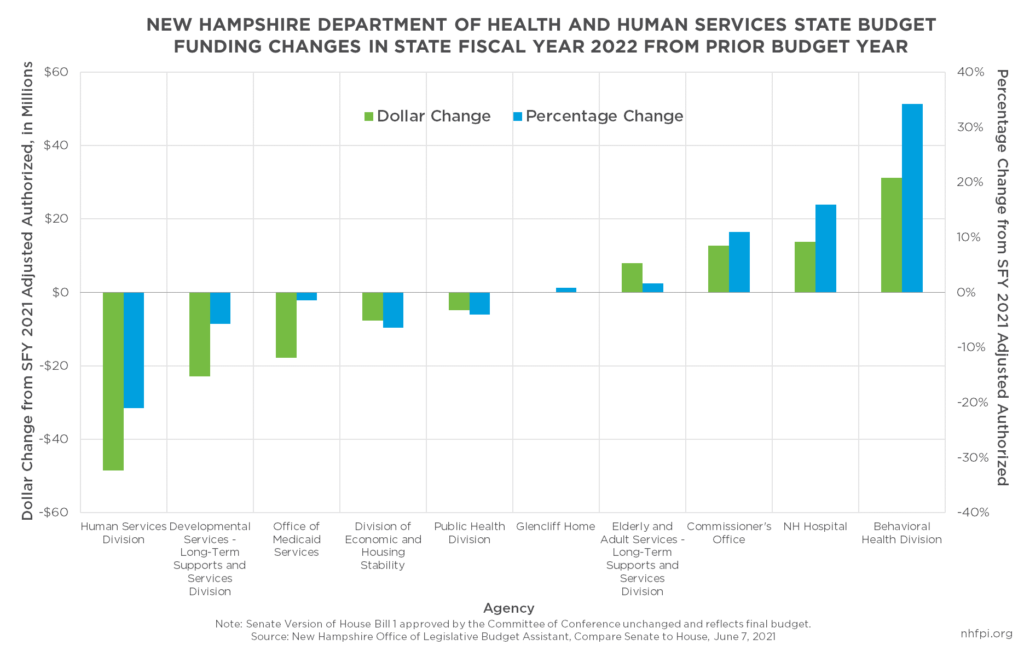

Within the budget of the DHHS are separate agencies, including divisions, offices, and institutions. These agencies each operate significant portions of the services provided by the DHHS, but vary in size substantially. The new budget increases funding for the DHHS in aggregate but does not increase funding across all divisions and agencies within the DHHS. Including Trailer Bill appropriations and back-of-budget reductions, the DHHS budget increases by $15.9 million (0.5 percent) in SFY 2022 relative to the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized, and another $37.4 million (1.3 percent) in SFY 2023 relative to SFY 2022.[8] However, funding levels are lower in key budget lines related to child care, developmental services, and Medicaid.

Human Services, Child Protection, and Child Care

The largest percentage decreases in funding at the agency level within the DHHS come in the Human Services Division, which sees a decline in funding by $48.4 million (21.0 percent) in SFY 2022 relative to the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized amount. The original DHHS Efficiency Budget request was also lower, albeit by a smaller amount, due to the reorganization of budget appropriation lines.[9]

A key change in this Division comes within the Division of Children, Youth, and Families, which is accounted for within the Human Services Division in the State Budget’s organization. Approximately $52.5 million that would likely have been in the Human Services Division budget for Out of Home Placement and Community Based Services appears in the Office of Medicaid Services budget as part of an apparent reorganization of line items.

The Division of Children, Youth, and Families also had a separate Trailer Bill appropriation of $1.5 million in State General Funds and Federal Funds to fund an additional ten Child Protective Service Worker positions. A provision of the Trailer Bill permits the DHHS to request funding for an additional 12 Child Protective Service Worker positions if those ten positions are filled during the biennium.

The Child Development Program in the Human Services Division saw a decline of $8.5 million (24.5 percent) between the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted levels and SFY 2022, and totaling about $15.2 million (22.7 percent) less during the new State Budget biennium relative to the prior State Budget’s allocations for two years. These reductions were in the budget line to support employment-related child care. The State Budget Trailer Bill includes a provision that authorizes the DHHS to draw funding from available Temporary Assistance to Needy Families federal funds if required to avoid a waitlist for these child care services, and requires quarterly reporting from the DHHS to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee on employment-related child care services. As the public health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis recede and more workplaces open, child care will provide an even more critical service than it did prior to the pandemic, enabling more Granite Staters to return to work while keeping their children safe.[10]

The new State Budget also establishes an Emergency Services for Children, Youth, and Families Fund to support DHHS efforts to avoid the removal of children from families and support reunification when no other supports or services are available to meet immediate needs. Parental reimbursement requirements for certain charges associated with children involved with DHHS programs or evaluations also have changed timelines, and certain charges can now be waived by the DHHS.

The budget also provides $600,000 in each year of the biennium, totaling $1.2 million, to the DHHS to fund community collaboration and parental assistance programs.

With an appropriation to the Department of Justice, the State Budget adds $500,000 to the Internet Crimes Against Children Fund during the biennium. The State Budget also includes a smaller increase in funding for the Office of the Child Advocate within the Department of Administrative Services.

Closure of the Sununu Youth Services Center

The State Budget requires the closure of the Sununu Youth Services Center (SYSC) by March 1, 2023. The SYSC is a secure institutional setting for individuals under age 18 who have been court ordered to such a setting and participate in behavioral programs.[11] In recent years, the number of individuals served by SYSC has been declining to a substantially smaller number than the facility’s capacity.[12]

All appropriations for the SYSC are accounted for in the Trailer Bill during the biennium, rather than by specific line items, which reduces the Human Services Division line as it appears in the Operating Budget Bill by $12.3 million in SFY 2022 relative to the SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amount.

The State Budget Trailer Bill includes language that establishes a committee to develop a plan for the closure and replacement or repurposing of the SYSC, including the cost estimates for the construction and operation of a new facility. The new facility must be designed to meet the unique needs of up to 18 youths at a time, and must be operational by March 1, 2023. The committee is required to produce a report by November 1, 2021, submit the plan to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee for approval, and prepare legislation for the 2022 Legislative Session relative to the implementation of the committee’s plan.

Developmental Services

The new State Budget reduces funding in SFY 2022 relative to the amount authorized for SFY 2021 for the Division of Developmental Services. Appropriations to the Division of Developmental Services decline by $22.8 million (5.7 percent) between SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted amounts and the SFY 2022 appropriations, although the funding increases from SFY 2022 to SFY 2023 by $36.9 million (9.9 percent).

The budget lines funding the developmental disability Medicaid home and community-based waiver services, managed under State contract by ten nonprofit Area Agencies, constitute the majority of funding within this Division, accounting for approximately 83.4 percent of the Division’s funding in SFY 2021. This budget line has been increasing in recent years, with the prior State Budget adding $127.8 million (25.0 percent) to the appropriations in the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget in an effort to avoid a waitlist for services. The new State Budget increases funding by only $26.8 million (4.2 percent) in the SFYs 2022-2023 biennium relative to the SFYs 2020-2021 biennium’s enacted budget. Without changes in funding sources from outside of the State Budget or significant shifts in the need for these services, policymakers will have to monitor for service waitlists to determine if this much smaller increase is sufficient to fund the services requested.

The State Budget also includes a $167,000 appropriation and any federal matching funds, targeting a five percent Medicaid reimbursement rate increase, to skilled nursing facilities and facilities providing intermediate care for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Office of Medicaid Services

The Office of Medicaid Services, which includes the budget lines for the State’s contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations, will see a decline in funding for SFY 2022 relative to the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized amounts.[13] Although several line items were shifted into the Office of Medicaid Services from other parts of the DHHS, most notably the Division of Children, Youth, and Families, reductions in funding elsewhere in the Office offset those additions. The SFY 2021 Authorized Adjusted budget included Federal Funds for the Medicaid to Schools program that the Legislature shifted out of the new budget, with the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee expected to accept those funds as needed during the biennium. The DHHS also revised its caseload estimates downward for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and made funding adjustments for expected changes in drug rebate revenue, State contracts, and federal policy. The new State Budget also adds $1.5 million specifically to comply with statutory requirements to support home visiting services.[14]

Economic and Housing Stability

The DHHS Division of Economic and Housing Stability has decreased funding levels in the SFY 2022 budget relative to SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized funding levels. This decrease of $7.7 million (6.4 percent) results in part from a reduction in funding for employment support program services, as well as a decline in expected payments to clients in the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program. The budget increases grant funding for the Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled program, and adds $1.3 million (11.1 percent) to the DHHS Bureau of Homeless and Housing Services between SFY 2021 and SFY 2022, maintaining the higher level of funding into SFY 2023.

Available affordable housing, both for rent and purchase, was severely constrained prior to the COVID-19 crisis; during the pandemic, housing prices have increased substantially and inventory has declined, leading to even fewer options for people with low and moderate incomes. Income losses have led many New Hampshire households to fall behind on rent and housing payments, which has likely increased needs for economic and housing assistance.[15]

Older Adults and Long-Term Care Services

The State Budget made several significant changes and investments to support long-term care. In these budgeted increases in appropriations, the Legislature avoided adding costs to counties, which are responsible for helping fund long-term care Medicaid costs for county residents.[16]

The State Budget boosts Medicaid reimbursement rates for the Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver (CFI) program, which provides care to individuals in their homes or communities and is designed to be an alternative to nursing home care.[17] This funding increases reimbursement rates for most CFI services by five percent. Services that are market- or manually-priced will not receive an automatic increase. Personal care services, homemaker services, case management services, and adult day medical care will receive boosts of more than five percent. Certain unspent funds from the current budget biennium will also be deployed to support the direct care CFI workforce with stipends, benefits, or other forms of direct compensation to staff.

The State Budget appropriates an increase of funds to nursing homes of five percent, totaling approximately $21.4 million in both General Fund contributions and matching federal dollars, while not requiring counties to provide additional dollars; had the counties been required to contribute, those funds would likely have been raised from property taxes. Language in the Trailer Bill also limits the growth of future county obligations for funding these services to two percent annually.

To help fund some of these changes, the State Budget makes available an estimated $11.0 million in appropriations from the current State Budget that had not been fully expended for both CFI and nursing home services in SFY 2022. In addition, the State Budget adds a total of $4.0 million, including both State and federal funds, for adult medical day services.

The State Budget’s Trailer Bill also establishes a committee to study reimbursement rate parity in several Medicaid waiver programs.

The new State Budget requires that, during the budget biennium, the income eligibility threshold for adult clients of the Social Services Block Grant program would increase each January. That increase will correspond to the cost-of-living adjustments made to Social Security benefits under federal law. The DHHS will also be exempt from certain rulemaking requirements relative to the cost-of-living adjustments as long as recipients receive proper notice that their income levels have been adjusted.

The State Budget suspends the Senior Volunteer Grant Program, which provides stipends and covers expenses for volunteers in senior companion and foster grandparent programs, during the budget biennium.[18]

Mental Health Services

The new State Budget increases funding at New Hampshire Hospital. This increase of $13.8 million (15.9 percent) between the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized total and the SFY 2022 budget is driven primarily by an increase in the budget for contracts for program services and personnel working in Acute Psychiatric Services.

The new State Budget appropriated $30.0 million from SFY 2021 surplus General Fund dollars to support the construction of a forensic psychiatric hospital. This allocation adds funding to the $8.75 million appropriation in the previous State Budget, set aside to construct a 24-bed facility on the grounds of New Hampshire Hospital; cost estimates for this facility have reportedly increased. This new hospital is planned to include space for individuals currently held at the Secure Psychiatric Unit at the State prison.

The new State Budget allocates $6.0 million during the biennium, also drawing from SFY 2021 surplus funds, to support enhanced reimbursement rates for transitional housing beds and to support new transitional housing beds for forensic patients and those with complex behavioral health conditions. The DHHS can also draw on certain past appropriations from the prior State Budget to fund these supports as well.

The new State Budget adds $3.0 million for community mental health program stabilization services, and approximately $5.2 million the system of care funds to support mobile crisis response team costs and non-Medicaid payments.

Separately, the State Budget appropriates $1.5 million to support services for veterans struggling with mental health and social isolation. This appropriation, although it funds a mental health service, is made to the Department of Military Affairs and Veterans Services.

Substance Use Disorder Services

The Division of Behavioral Health Services has an increase in funding of $31.2 million (34.2 percent) between the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized appropriation and the SFY 2022 State Budget appropriation.

The Bureaus of Children’s Behavioral Health and Mental Health Services are both within this Division as well, and both see increases in funding. The Bureau of Mental Health Services budget is supported by certain appropriations addressed above, and the Bureau of Children’s Behavioral Health decreases from SFY 2021 to SFY 2022.

Of the total increase at the Division, $21.8 million of the increase occurs in the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services. The increase is due to a boost in funding through the State Opioid Response Grant from the federal government, although the State Budget does increase State General Fund support to the Bureau by a smaller amount.

Additionally, the State Budget transfers the Controlled Prescription Drug Health and Safety Program from the Office of Professional Licensure and Certification to the DHHS.[19]

Related to substance use disorders and outside the DHHS budget, the new State Budget provides $3.1 million in additional funding to the Department of Safety to fund overtime costs at the State Police and State forensic laboratory related to narcotics-related investigations, and to disburse funds to counties and local governments in support of overtime costs within the Substance Abuse Enforcement Program.

Back-of-Budget Reduction for Positions

The State Budget includes a back-of-budget reduction to appropriations for the DHHS. This reduction focuses on removing positions that are funded but are currently vacant. The total reduction during the budget biennium would be $22.6 million in General Fund appropriations, without specifying amounts for individual budget years. This reduction eliminates approximately 226 positions and limits the DHHS to having no more than 3,000 full-time authorized positions during the biennium. The DHHS is required to report to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee in each September of the biennium as to which budget lines will be reduced for the reductions made in that fiscal year.

Appropriation for Financial Review Recommendations

The State Budget appropriates $3.3 million to implement certain recommendations from the financial review conducted by the management consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal. These funds will support the streamlining of certain agency operations to support greater efficiency and accountability, according to the statutory language. The language also identifies certain transformation projects over a four-year period, although the funding would be available only through the State Budget biennium, and could be supported by applicable federal funds and any gifts, grants, or donations for this purpose. Alvarez & Marsal began working with the DHHS during 2020 to conduct a strategic assessment of DHHS operations, produce cost savings, increase efficiency, improve service delivery, and consider the operational and financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.[20]

Restrictions on Abortion Services and Family Planning Operations

Although not within the purview of the DHHS or necessarily having a direct impact on State finances, the State Budget includes restrictions on certain reproductive health care services in the Trailer Bill. The State Budget language bans all abortions after 23 weeks of pregnancy, except in cases of a medical emergency that presents serious risk of substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function of the pregnant woman, including death. Health care providers who knowingly perform an abortion 24 weeks or later into a pregnancy will be guilty of a felony. Providers must perform ultrasounds before performing an abortion, and have reporting requirements associated with performing abortions. The language includes a severability clause that maintains other portions of the statute if portions of the law are ruled invalid.

The State Budget also requires that any State contract awarded for family planning projects shall require that no State funds be used for abortions, directly or indirectly, and that annually the DHHS will inspect a contracted family planning operation’s records to ensure compliance with this requirement. The DHHS must certify that no funds are being used for abortion services each year. If the DHHS cannot certify that no funds are being used for these purposes, or if the Governor and Executive Council find that State funds have been used for abortion services based on information presented by the DHHS, then the family planning operation would either forfeit all right to receive further funding or would have to suspend all operations until the family planning project is physically and financially separate from the reproductive health facility.

The State Budget includes $50,000 to provide incentive funding for first-time family planning contract awardees, which is required to not exceed $10,000 per contracted entity.

Other Health and Human Services Changes

The Senate voted to make several other changes to funding and policy at the DHHS, including:

- creating and funding an incentive for enrollees in the Food Stamp Program, also known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), by providing a dollar-for-dollar match for SNAP beneficiaries for fresh fruits and vegetables, with an emphasis on locally grown food, at farmer’s markets, farm stands, and other food retailers

- funding a youth outreach program relative to tobacco use prevention and cessation

- limiting expansion of closed loop referral systems until the use of these systems and privacy concerns can be addressed by a legislative oversight committee

Local Public Education

The State Budget includes significant changes to funding for local public education. The State Budget projects lower student enrollment, which decreases the aggregate appropriations made through the Adequate Education Aid funding formula. The new State Budget also discontinues the one-time funding targeted at communities with lower taxable property values per student included in the prior State Budget. Those changes will reduce funding for local public education in aggregate in the new State Budget relative to the prior State Budget. However, the new State Budget adds significant new targeted aid funding for school districts with higher concentrations of low-income students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, and adds resources for temporary adjustments to funding for districts that experienced lower enrollment during the pandemic.

Temporary Boost to Enrollment-Based Aid

The new State Budget limits the financial impact of the drop in enrollment in public schools on State-provided aid. The total number of pupils in New Hampshire public schools declined about 4.2 percent between the 2019-2020 school year and the 2020-2021 school year.[21] This drop in enrollment continues a trend of declining overall enrollment, but was likely substantially exacerbated by the pandemic in a temporary fashion. State aid to local public schools in New Hampshire is largely based on enrollment, as the Adequate Education Aid formula allocates funding on a per pupil basis.[22]

Greater flexibility in federal free and reduced-price school meal programs was granted during the pandemic, which broadened eligibility and allowed school districts to provide meals to students, often at their homes, without the previously required processes for verifying family income eligibility. As a result, the official counts for free and reduced-price school meal eligibility, which is also used to distribute additional targeted aid to communities with more children from families with low incomes, dropped significantly even as household incomes from work also dropped in New Hampshire.[23] Between the 2019-2020 school year and the 2020-2021 school year, State-identified free and reduced-price school enrollment eligibility dropped by 11,058 students (24.2 percent).[24]

The State Budget permits schools to use the higher enrollment figures of either the 2019-2020 school year, before the pandemic, or the 2020-2021 school year for determining enrollment-based State aid for the 2021-2022 school year. Schools can use both total enrollment figures and free and reduced-price meal enrollment from before the pandemic for these calculations. The budget also includes provisions for using a modified baseline for measuring third-grade reading scores for the purposes of State education aid, and includes policy language that extends the enrollment-based hold-harmless policy for funding specific to free and reduced-price school meal enrollment into SFY 2023; if the federal waiver on certain enrollment-related requirements for free and reduced-price meal programs is extended, then enrollment figures could be artificially suppressed again, and school districts will be able to continue relying on pre-pandemic figures for State funding purposes. These enrollment-based provisions will add approximately $45.7 million in appropriations for local public schools in SFY 2022.[25]

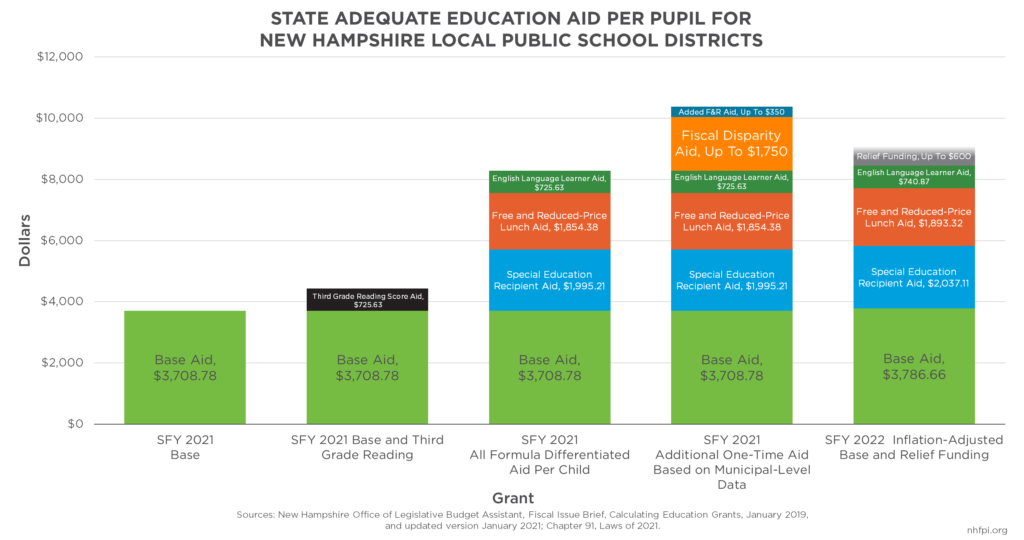

Adequate Education Aid and Relief Funding

The primary mechanism through which State funding is supplied to local public schools for supporting education is Adequate Education Aid. The majority of this assistance comes in the form of per pupil Adequate Education Grants, which include base grants of $3,786.66 per full time student in SFY 2022, with additional per pupil funding for students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, students receiving special education assistance, and English language learners.[26] In the 2019-2020 school year, New Hampshire local public school districts reported average operating expenses of $16,823.88 per pupil, with added costs of tuition, transportation, facility purchase or construction, capital costs, and interest bringing the total average per student cost to $19,788.15.[27]

Adequate Education Aid also includes Stabilization Aid, which was established as a method of offsetting the negative impacts on some communities of a significant revision of the per pupil education formula that took effect in SFY 2012.[28]

The State Budget establishes “Relief Funding” for school districts in addition to the baseline Adequate Education Aid funding formula. This Relief Funding is constructed with a similar method to a component of the one-time aid in SFY 2021 under the prior State Budget. The Relief Funding targets more aid to school districts with higher concentrations of free and reduced-price school meal-eligible students. These students come from families with low incomes, typically with incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or less than $40,626 for a family of three in 2021, to be eligible.[29] The additional amount of aid to school districts per student aid is allocated on a sliding scale, and may be as high as $600 per eligible pupil for districts with more than 48 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals. Districts with less than 12 percent of students eligible for this assistance will not receive additional aid. The total appropriations are capped at $17.5 million per year in aggregate in the new State Budget, with amounts to each individual district pro-rated to match that total; as a result, the additional amount per student may not reach $600, the figure identified in the new statute as the amount of additional Relief Funding to be provided to the school districts with the highest percentages of students in need. The one-time aid in SFY 2021 that is similarly structured also used a sliding scale from 12 percent to 48 percent, and provided a maximum amount of additional aid of $350 per eligible student; this formula provided an additional $11.7 million in targeted aid to school districts in SFY 2021.[30]

The $35.0 million appropriation to support this Relief Funding will be shifted out of the Education Trust Fund’s SFY 2021 surplus and moved to a special account, and is separated from the traditional Education Trust Fund expenditures for Adequate Education Grants. Future appropriations may be funded through different mechanisms, if this targeted Relief Aid continues into future budget biennia.

School Building Aid

The State Budget provides an additional $30.0 million for the school building aid program. The appropriation is dedicated to funding new projects. These funds were drawn from the SFY 2021 surplus. The Department of Education reports there are about $104.2 million in school building aid applications for SFYs 2022 and 2023, and the backlogged project costs are substantially higher from applications ranging from 2011 to 2020 that have not been funded by the State.[31]

The State Budget also adds $2.0 million the Public School Infrastructure Fund during the biennium. The aid provided to local school districts by the Public School Infrastructure Fund is directed by the Governor, in consultation with the Public School Infrastructure Commission, which is comprised of elected and appointed public officials. The Fund’s resources are deployed for certain types of projects, including safety upgrades, fire code compliance changes, fiber optic connections, compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and emergency readiness. Most of these projects have been relatively small projects, compared to the school building aid requests, that were designed to improve the security of school buildings.[32] The State Budget explicitly expands the scope of projects funded by the Public School Infrastructure Fund to include energy efficient school buses.

Compliance with Federal Requirements

The State Budget requires the State to comply with federal maintenance of effort and equity requirements associated with school funding and required by the American Rescue Plan Act.[33] No additional funding was budgeted to maintain this compliance, which is based on funding levels from prior years and is a requirement of receiving certain federal assistance. The State Budget proposal establishes a mechanism through which the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the New Hampshire Department of Education will make any needed adjustments during the biennium to maintain compliance.

Education Freedom Accounts

The State Budget includes a major shift in education funding policy. This policy permits parents who disenroll their children from school districts to apply for and receive the Adequate Education Aid funding the school district would have received to support that student in an “Education Freedom Account.” Money in this Account may be used by parents for a wide variety of education expenses, including tuition and fees at a private school, Internet services and computer hardware primarily used for education, non-public online learning programs, tutoring, textbooks, school uniforms, certain therapies, and other expenses approved by a State-recognized approved scholarship organization.

To be eligible, a student must be a state resident eligible for public school from a household with an annual household income at 300 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or below at the time of application. However, that student’s household does not need to maintain incomes below that level to continue to be enrolled and receive funding through the Education Freedom Account.

School districts will no longer receive this Adequate Education Aid, but the State will supply two years of transition funding after the student departs the district and begins receiving funding in an Education Freedom Account. Districts will receive 50 percent of the original amount for the newly-disenrolled student in the first following school year, and 25 percent in the second year. The grant will disappear after the second year following a student’s transition to using an Education Freedom Account. These transition grants will not be provided to school districts for students who disenroll after July 1, 2026.

The potential cost of this Education Freedom Account policy is difficult to project, as it is dependent on the number of currently homeschooled and private-school pupils that are eligible and apply for an Education Freedom Account as well as the number of students whose parents disenroll them from public schools and transition to use of these Accounts. The Department of Education assumed relatively low enrollment in Education Freedom Accounts during the next two years for the purposes of the new State Budget’s projections, which results in a projected cost to the Education Trust Fund of $3.45 million during the biennium.

Statewide Education Property Tax Reduction and Refunds

The State Budget includes a reduction in the Statewide Education Property Tax (SWEPT) of $100 million for SFY 2023. The SWEPT is a State tax that supports the Education Trust Fund. The State requires local governments to collect this property tax in their jurisdictions, based on calculations conducted by the Department of Revenue Administration, to raise money to support local public education and offset a certain portion of the State’s statutory obligation to fund local public education under the education funding formula. The State does not collect any revenue from the SWEPT; all money is raised and retained locally. The State calculates the amount to be collected by each jurisdiction based on an estimate of taxable property value statewide and the target amount to be collected statewide.[34]

While the reduction of $100 million in the targeted amount to be raised by the SWEPT is primarily a revenue source change for the Education Trust Fund, it functionally provides more resources from other Education Trust Fund revenue sources to local governments, potentially relieving upward pressure on local property taxes.

The State Budget includes a provision that provides an estimated $15.3 million to communities that have substantial amounts of property wealth per student.[35] These are communities that generate more revenue than is needed to support the State’s Adequate Education Aid obligations when the SWEPT statewide rate is applied to their communities. Under current law, these communities can keep those excess SWEPT dollars locally, rather than paying them to the State under this tax, as long as the dollars are used to support education. The estimated $15.3 million appropriation in the State Budget will provide aid to these relatively property-wealthy communities to offset the loss of excess SWEPT revenue, which is beyond the amount obligated to these communities by the State under the Adequate Education Aid formula.

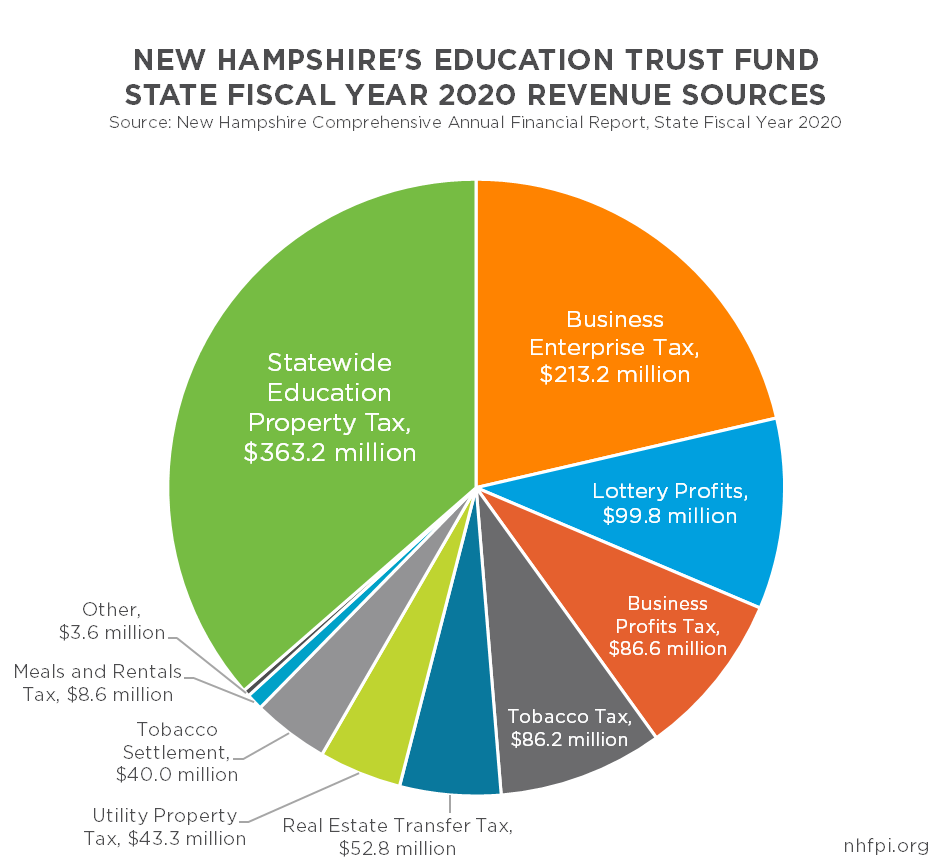

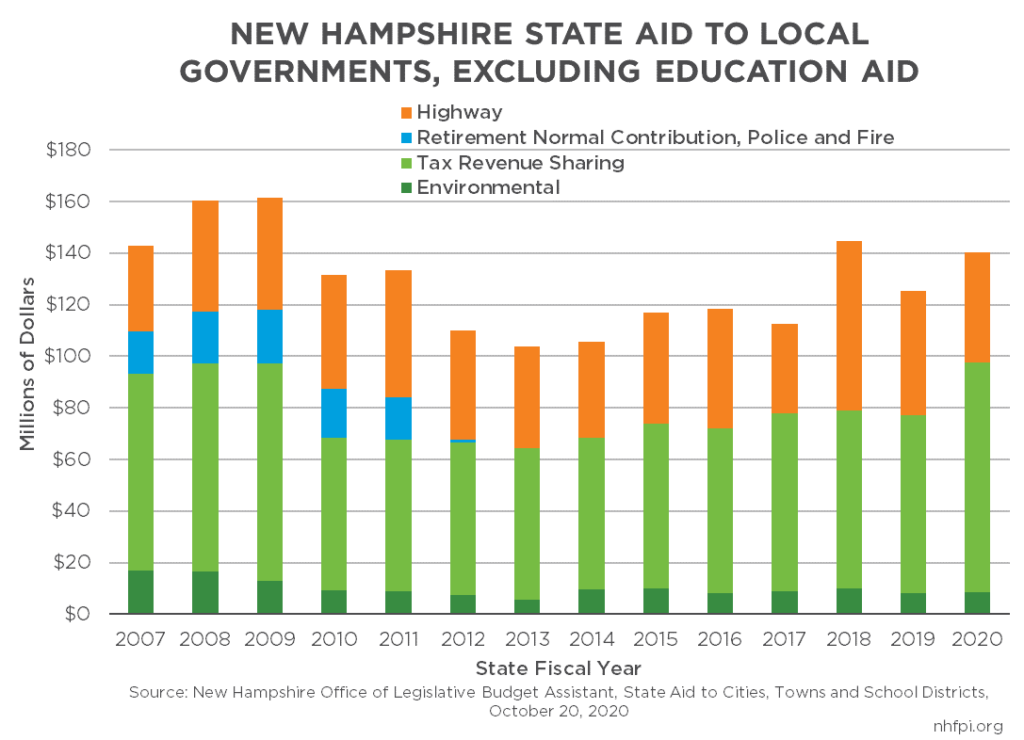

Non-Education Aid to Municipalities

Aid for local public education is the most significant transfer of resources from the State to local governments, but other assistance to municipalities and counties has a significant role in local budgets. Local property taxes account for more than half of all local government revenue in New Hampshire, while State grants constitute about a quarter of all revenue, and federal funding has a much smaller role. The total statewide tax commitment for local property taxes in Tax Year 2020 was about $3.7 billion; the State’s single largest tax revenue source, the Business Profits Tax, only collected about one-eighth of that amount of revenue in SFY 2020.[36] State aid to local governments that is not related to education includes funds for highway and bridge construction and highway block grants; environmental aid associated with water systems, pollution and flood control, and landfill closures; and general revenue sharing from Railroad Tax and Meals and Rentals Tax revenues. State aid to local governments for education totaled $1,048.3 million in SFY 2020, while non-education aid totaled about $140.5 million.[37]

The State Budget increases aggregate non-education aid to local governments relative to the prior State Budget, although the funding mechanisms change, and communities with more children with low incomes may receive less aid than appropriated to them by the prior State Budget. The State will distribute more aid to municipal governments through the Meals and Rentals Tax revenue sharing. Prior to the enactment of the State Budget, statute required that a catch-up formula be used to eventually share 40 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax revenue with municipal governments on a per capita basis, as the State has shared much less than that 40 percent amount during the last decade. The formula has been suspended for most years since the Great Recession of 2007-2009.[38]

The new State Budget eliminates the catch-up formula and the 40 percent pledge, instead setting the shared amount to 30 percent and fully funding that smaller share. This change results in approximately $50.6 million more than was distributed through in Meals and Rentals Tax revenue in the prior State Budget during the biennium.

The prior State Budget included targeted one-time grants, totaling $40.0 million, in municipal aid through a different formula, which was based primarily on student populations and weighted heavily toward the relative numbers of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals. These payments are not repeated in the new State Budget.

The new State Budget requires that all Meals and Rentals Tax revenue shared with cities and towns be deposited into a separate fund. This change moves a total of approximately $188.2 million in expenditures that would otherwise appear in the SFYs 2022-2023 expenditures out of the State Budget entirely.

The new State Budget uses $15.6 million from SFY 2021 General Fund surplus dollars to support State aid grants for payments on existing grants for municipal water and pollution control infrastructure projects. As part of the Substance Abuse Enforcement Program, the budget also added $2.4 million in grants to county and local law enforcement agencies from the Department of Safety from SFY 2021 surplus dollars.

The new State Budget also alters State law to permit municipalities to accept funds from the federal government provided by the American Rescue Plan Act.[39]

Higher Education

Funding for public higher education institutions remained relatively consistent with the prior budget in the new State Budget. Both the University System of New Hampshire and the Community College System of New Hampshire receive support from the State in the form of grants from the General Fund to help fund operations, and are maintained as separate entities in the new State Budget.

The funding level for the University System of New Hampshire is $88.5 million per year in the new State Budget, the same amount as the SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized level. The University System did receive one-time aid of $9.0 million in SFY 2020 to support nursing, occupational therapy, and speech and language pathology programs, while also having a baseline General Fund grant level of $85.5 million in SFY 2020. The new State Budget does not have any one-time appropriations to the University System, but keeps the funding levels the same as SFY 2021 in each year of the biennium, which was the highest amount of General Fund support since SFY 2011.

The Community College System of New Hampshire similarly received both increasing General Fund contributions and more one-time aid in the prior State Budget. The new State Budget slightly boosts support, from $55.36 million in SFY 2021 to $56.0 million in SFY 2022, and holds that amount steady in SFY 2023. The new State Budget also shifts administration of the Dual and Concurrent Enrollment Program from the Department of Education to the Community College System, and appropriates a dedicated $1.5 million per year to the Community College System for the program.

The State Budget also adds $6.0 million to the Governor’s Scholarship Fund, which supports the Governor’s Scholarship Program and awards up to $2,000 per year for eligible students toward the cost of a post-secondary education or training program in New Hampshire. The State Budget shifts administration of the Governor’s Scholarship Program from the Office of Strategic Initiatives, which was dissolved with the creation of the Department of Energy, to the New Hampshire College Tuition Savings Plan Advisory Commission.[40]

Housing and Homelessness

The State Budget appropriates $25.0 million to the Affordable Housing Fund in a one-time appropriation. The Fund will receive an additional $10.0 million in the two years of the State Budget from a dedicated $5.0 million per year appropriation from the Real Estate Transfer Tax, a policy that was first established in the prior State Budget. The Fund, which is administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority, provides grants and low-interest loans for building or acquiring housing affordable to people with low-to-moderate incomes. This $25.0 million appropriation drew from the SFY 2021 General Fund surplus.

The State Budget also boosts funding for the Shelter Program at the DHHS Bureau of Homeless and Housing Services by $3.0 million in General Fund appropriations during the biennium.

The State Budget also requires that a commission, established by the State Budget and intended to study limiting the carry over of credits from overpaid taxes by Business Profits Tax and Business Enterprise Tax filers, consider whether a business tax credit or other type of credit could be used to incentivize affordable housing development.

Transportation

The pandemic’s negative impacts on transportation-related revenues have been more durable than those on other key revenue sources for New Hampshire, including General Fund and Education Trust Fund revenue sources. The new State Budget funds the New Hampshire Department of Transportation at levels only slightly higher than the aggregate levels from the two years of the prior budget biennium, with an increase of $3.8 million (0.3 percent), including Trailer Bill appropriations. Funding levels for SFY 2022 are above SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized levels, due in part to the one-time appropriation of General Funds made in the Trailer Bill, while funding levels specific to SFY 2023 fall back below SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized levels. However, the one-time Trailer Bill appropriations may also be deployed in SFY 2023. The State Budget made a significant deposit into the Highway Fund to support future solvency.

In specific budget lines, the Department of Transportation has declines in funding for construction and repair materials and certain highway operations in the new State Budget relative to SFY 2021 Adjusted Authorized levels. However, there were significant appropriations of General Fund dollars in the Trailer Bill for certain purposes.

The State Budget’s Trailer Bill appropriates $6.0 million for the acquisition of fleet vehicles and equipment. The budget also includes a $5.0 million appropriation for highway and bridge betterment, which may contribute to construction and repair materials costs as well. A separate provision in the State Budget appropriates an additional $5.0 million to the Department of Transportation for SFY 2022 alone to leverage federal discretionary grants that require a State cash match.

The Department of Transportation is not continuing the Conway Bypass project, and the State has previously drawn federal money for work on that project. The State Budget appropriates $7.0 million to the Department of Transportation to repay the federal government, but language in the Trailer Bill specifies that the Department is expected to continue negotiating with the federal government to build a specific payback plan.

The State Budget allocates $3.25 million to reconstruct and reclassify nearly two miles of Calef Hill Road in Tilton. The budget Trailer Bill also includes language that permanently removes the toll booths from the northbound and southbound ramps of Exit 10 on the F.E. Everett Turnpike in Merrimack.

A provision in the State Budget enables remaining funds from a $20 million appropriation to address structurally deficient bridges, originally made in 2018 from General Fund surplus, to lapse to the Highway Fund as of the end of SFY 2021. Lapsing this revenue to the Highway Fund will allow these dollars to be used for other road and highway-related costs.

Finally, the State Budget appropriates $50.0 million in General Fund SFY 2022 dollars to the Highway Fund. The Highway Fund would have balanced without the infusion over the biennium, according to the Highway Fund Surplus Statement, but would have been diminished to a total of approximately $604,000. This appropriation boosts the estimated total at the end of the biennium to $50.6 million.[41]

Other Initiatives

The State Budget includes significant policy changes in other areas, including substantial modifications to both fiscal policies and other areas that have little or no connection to State finances.

Certain Restrictions on Teachings and Trainings

The State Budget includes policy language restricting public teaching and training programs from using certain speech related to systemic racism and sexism. The language prohibits public employers, including the State government, municipal governments, and school districts and administrative units, from instructing or training that any person or group is inherently superior or inferior to another based on their age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, creed, color, marital status, familial status, mental or physical disability, religion, or national origin. These public employers are also forbidden from teaching that anyone, by virtue of these characteristics, is consciously or unconsciously inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, and from teaching that people cannot or should not treat each other equally or without regard to these characteristics.

Public employees are protected from discipline for refusing to participate in trainings that teach these ideas, and students will not be taught these ideas in public school. Educators who engage in these types of teachings will be considered in violation of the Educator Code of Conduct and potentially face disciplinary sanction by the State Board of Education.

Family Medical Leave Insurance

The State Budget establishes the Granite State Family Leave Plan, which will be a required plan for State employees and a voluntary plan for other entities seeking to join, such as businesses and individuals. State employees will participate with the State paying the costs. Non-state employers may join under certain conditions, and may choose the extent to which their employees are required to contribute to the cost of participation. Procedures for participation are different for employers with fewer than 50 employees. The program will be overseen by the Department of Administrative Services, which will contract with a private accident or life insurance carrier to run the program. There is no appropriation to support startup costs for this program.

Eligible employees will receive 60 percent of their average weekly wage for a maximum of six weeks per year, with a cap on the wage calculation for higher income earners. Employees will be eligible as the result of the birth of a child or placement of a foster or adopted child within the past year, a serious health condition of a family member, or for certain military-related care. The health condition of the employee is not a cause for eligibility, although caring for ill children, parents, or a spouse would trigger eligibility.

The insurance program’s stabilization would be supported in part by diverting Insurance Premium Tax revenues associated with this family medical leave insurance. The State will also offer a tax credit against the Business Enterprise Tax for participating businesses for up to 50 percent of the premium paid by a sponsoring employer.

Elimination of Unfilled State Employee Positions

The State Budget requires that State agencies abolish all classified, full-time positions that were vacant prior to July 1, 2018 and remain vacant as of July 1, 2021. If a person is about to be hired into one of those positions and an offer for employment has been accepted, that position will not be eliminated. Executive branch agencies must supply the list of positions to be abolished to the Department of Administrative Services by September 1, 2021. The Department must then supply a written report of the positions abolished and the funds transferred, some of which would be required to support funds related to employee salaries and benefits, to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. The Governor may grant individual exemptions to this policy.

Limitations on Governor’s Emergency Powers

The State Budget includes language altering the Governor’s emergency powers relative to previous statute. Under these new limitations, the Governor retains the previous authority to declare and renew a 21-day State of Emergency, but must inform the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate about the impending issuance of Emergency Orders under the State of Emergency. The new language explicitly empowers the Legislature to terminate a State of Emergency with a majority vote of both chambers, requiring a majority of legislators be present in each.

The Governor will be required to call and address a joint session of the Legislature to convene 90 days after the declaration of State of Emergency, and every 90 days thereafter; at this meeting, both chambers of the Legislature will be required to independently vote on a resolution that would end the State of Emergency.

Members of the Legislature are also exempt from any Emergency Orders that would infringe on their ability to travel and conduct their legislative business.

The Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee will be required to approve any federal, private, or other non-state gift, grant, or loan for the purposes of the State of Emergency over $100,000, but the Governor will have the authority to accept and expend the funds if the Committee did not accept or reject the items within five days. The Governor will have certain expenditure authorities immediately in situations requiring emergency action for the health, safety, and welfare of citizens. The Governor will have to notify the Senate President, Speaker of the House, and Chair of the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee within 24 hours of such expenditures.

Other Provisions

The State Budget includes several other key provisions, including:

- creating the Department of Energy, combining components of the energy-related components of the Office of Strategic Initiatives with the Public Utilities Commission, the Office of the Consumer Advocate, and the Site Evaluation Committee

- shifting the planning components of the former Office of Strategic Initiatives to a new office within the Department of Business and Economic Affairs

- raising pay for certain State employees, including legislative and judicial staff and certain officials and employees in the Executive Branch, as well as a boost in longevity bonus pay for State officials, State Police Troopers, and classified employees

- appropriating $10.0 million to help investors who suffered financially due to the Financial Resources Mortgage fraud

- appropriating $3.0 million to the Department of Education for a State student data collection and reporting system

- allocating a total of $2.2 million additional funds to travel and tourism development and marketing efforts in two separate lines at the Department of Business and Economic Affairs

- suspending the distribution of 3.15 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax revenues to the Division of Travel and Tourism Development during the biennium

- establishing a body-worn and dashboard camera fund to provide matching dollars for local law enforcement agencies purchasing camera equipment, and providing $1.0 million in funding for SFY 2022, as well as $720,000 for body-worn cameras for corrections, probation, and patrol officers at the State Department of Corrections

- creating a commission to craft proposed legislation for an independent statewide entity to receive complaints regarding sworn and elected law enforcement officers

- establishing two funds, likely to serve as frameworks for providing flexible federal aid from the American Rescue Plan Act, for businesses with 10 or fewer employees and for public venues

- exempting the Department of Administrative Services from complying with the recommendations of certain performance audits conducted by legislative staff and requirements in existing Executive Orders regarding energy efficiency and monitoring of energy use, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions

- maintaining expanded powers for the Department of Administrative Services to consolidate human resources, payroll, and business processing positions and functions across the State’s agencies

- permitting the Governor, with the approval of the Executive Council, to sell, lease, rent, transfer, or otherwise dispose of the former Laconia State School property

Revenue Policy Changes

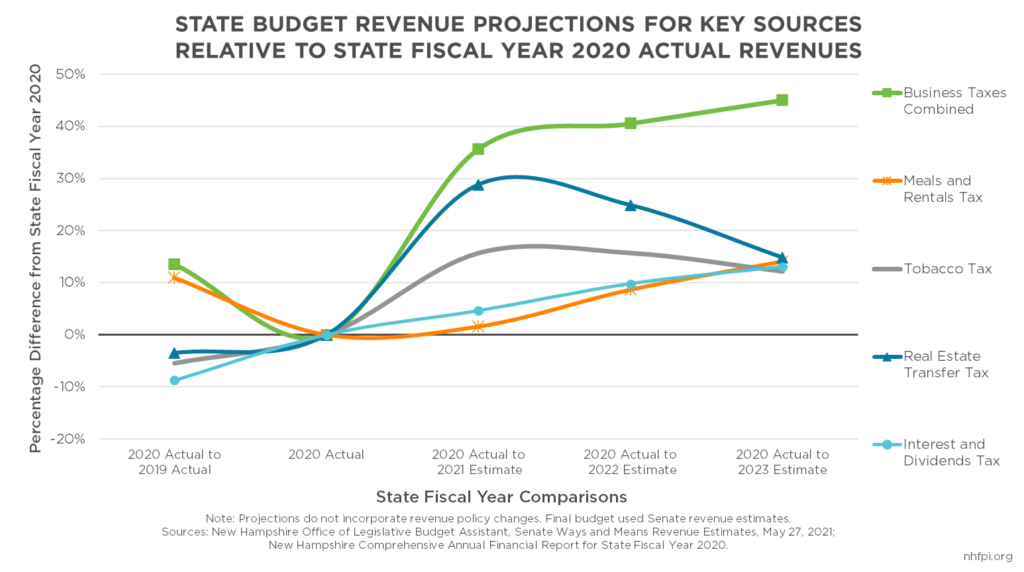

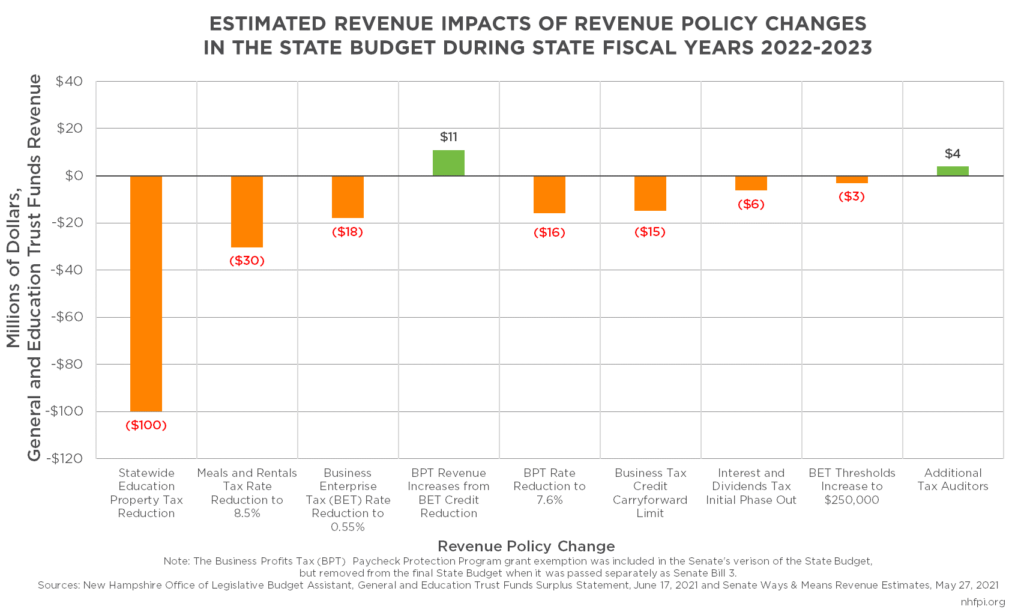

The new State Budget makes significant changes to tax policy. The tax policy changes in the State Budget’s Trailer Bill are estimated to reduce revenue to the State of New Hampshire’s General and Education Trust Funds by $177.7 million during the biennium, and hundreds of millions more in subsequent years. Paired with other tax policy changes passed separately, the tax policy changes were projected in by legislators in the budget process to reduce revenue, relative to no policy changes, by approximately a quarter of a billion dollars during the biennium.

The State Budget itself can grow in appropriations and remain balanced despite these significant revenue reductions because the Legislature’s revenue projections, incorporated into the State Budget, anticipate substantial revenue growth over the next two-year period. The Legislature projected that General and Education Trust Funds revenues during the SFYs 2021-2022 time period would exceed actual revenues collected in the SFYs 2019-2020 time period by $656.1 million (12.7 percent), and that revenues in the SFYs 2022-2023 budget biennium would exceed SFYs 2019-2020 revenues by $742.2 million (14.4 percent).

The Legislature projected this substantial growth would stem from rapid and strong increases in key tax revenue sources relative to both their pandemic lows and the years immediately preceding the pandemic. The Legislature projects that, by SFY 2023, the Business Profits Tax (BPT) and Business Enterprise Tax (BET) combined receipts will be $224.0 million (27.8 percent) higher than pre-pandemic receipts in SFY 2019. The Legislature also projected that the Interest and Dividends Tax will collect $27.4 million (23.9 percent) more revenue in SFY 2023 than it did in SFY 2019. The Legislature projected a recovery for the Meals and Rentals Tax, following depressed revenues during the pandemic, but that Real Estate Transfer Tax and Tobacco Tax revenues would both decline in future years while remaining above their pre-pandemic levels.[42]

Business Tax Changes

The State Budget makes several significant changes to the State’s two primary business taxes, the BPT and the BET. Paired with two other changes passed in separate bills, the State Budget will significantly reduce revenue collected through these two business taxes relative to previous policy.

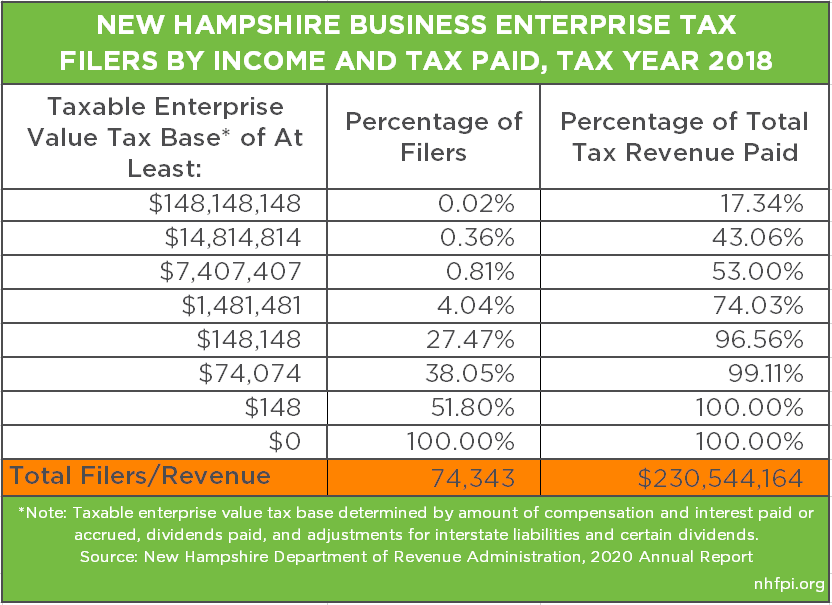

The State Budget reduces the BET tax rate from 0.60 percent to 0.55 percent beginning in Tax Year 2022. About 90 percent of businesses have a Tax Year that coincides with the Calendar Year.[43] The BET is based on compensation and interest paid or accrued and dividends paid. Unlike the BPT, a business entity does not need to be making a profit to have a BET liability. While the BET has a broader base than the BPT, the tax still draws significantly from larger business entities; 0.81 percent of filing businesses in Tax Year 2018 paid 53.0 percent of the tax revenue collected in that year. The State Budget’s projections suggest the BET rate reduction will lead to about $18.0 million less revenue to the General and Education Trust Funds over the course of the biennium.

The State Budget also raises both existing BET filing thresholds to $250,000 in 2022, which will make the smallest entities less likely to need to file. The two thresholds are based on separate components of business activity. The current threshold for the BET’s actual tax base, comprised of compensation, interest, and dividends paid, is currently $111,000. Businesses have a separate filing threshold based on gross receipts, which is currently $222,000. The new State Budget raises, which the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration estimates will cost the General and Education Trust Funds approximately $3.1 million during the biennium.[44]

As the BET can be deployed as a dollar-for-dollar credit against the BPT, reducing the BET liability for businesses that do have a BPT liability causes those businesses to owe more in BPT. As a result, BPT revenues will increase, but not sufficiently to offset the loss in BET, as only businesses that have a profit would see their liabilities under the BPT increase. The estimated increase in BPT revenues incorporated into the State Budget’s projections is $10.9 million.

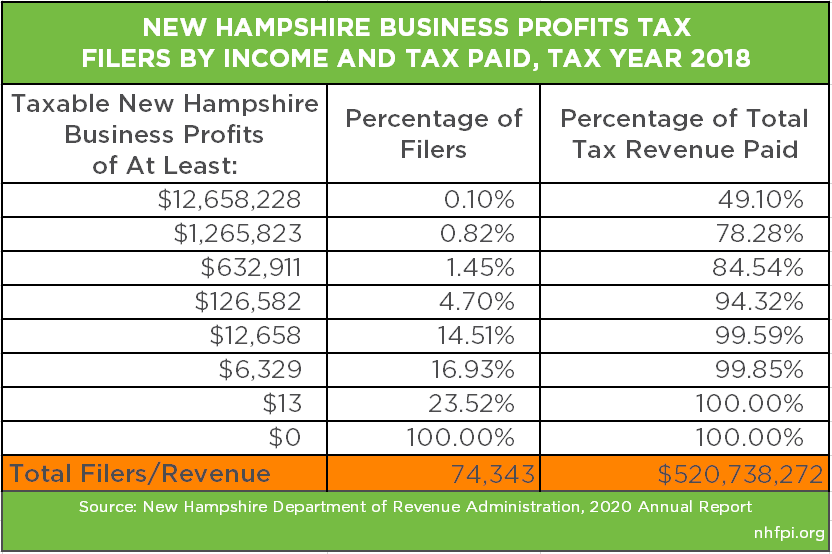

That increase is more than offset by a second business tax rate reduction in the State Budget. The rate for the BPT, the State’s largest tax revenue source, will be lowered from 7.7 percent to 7.6 percent starting in Tax Year 2022. Relative to the BET, a small number of profitable taxpayers pay the BPT. In Tax Year 2018, the most recent year with published data, 76 filers (0.1 percent of filers) paid 49.1 percent of all revenue collected by the BPT. These businesses had taxable profits attributable to New Hampshire activity of at least $12.6 million, with an average taxable profit of about $42.5 million under the New Hampshire BPT. If the BPT tax rate had been 0.1 percent lower in Tax Year 2018, the average tax liability reduction for these 76 most profitable entities would have been about $42,584.61 per filer. About 76.5 percent of all BPT filers do not owe any tax, likely due to credits such as BET payments. The reduction in the BPT rate from 7.7 percent to 7.6 percent is projected to reduce State revenues by $15.8 million during the biennium.

Two separate pieces of legislation passed during the 2021 Legislative Session will also reduce revenue from the BPT. One new statute will exempt federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) grants to businesses from the calculations of business income for purposes of the BPT. Many businesses applied for PPP loans, most of which were turned into grants, during 2020. Many of those businesses also made a profit during 2020. Under prior New Hampshire law, businesses were required to count PPP grants as income for the purposes of calculating profit. Businesses that made a profit, after other credits such as BET payments, would be taxed based in part on those PPP grant revenues. The new statute exempts the PPP grants from the calculation of business income for the purposes of the Business Profits Tax. This change is estimated to cost New Hampshire approximately $69.4 million during the biennium, according to the projections used by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant to inform the Legislature’s State Budget decisions.[45] The second piece of legislation raises the filing threshold for the BPT from $50,000 in gross business income to $92,000, likely exempting many small businesses from having to file and, based on estimates from Tax Year 2018, potentially reducing revenue by about $2.5 million.[46]

Interest and Dividends Tax

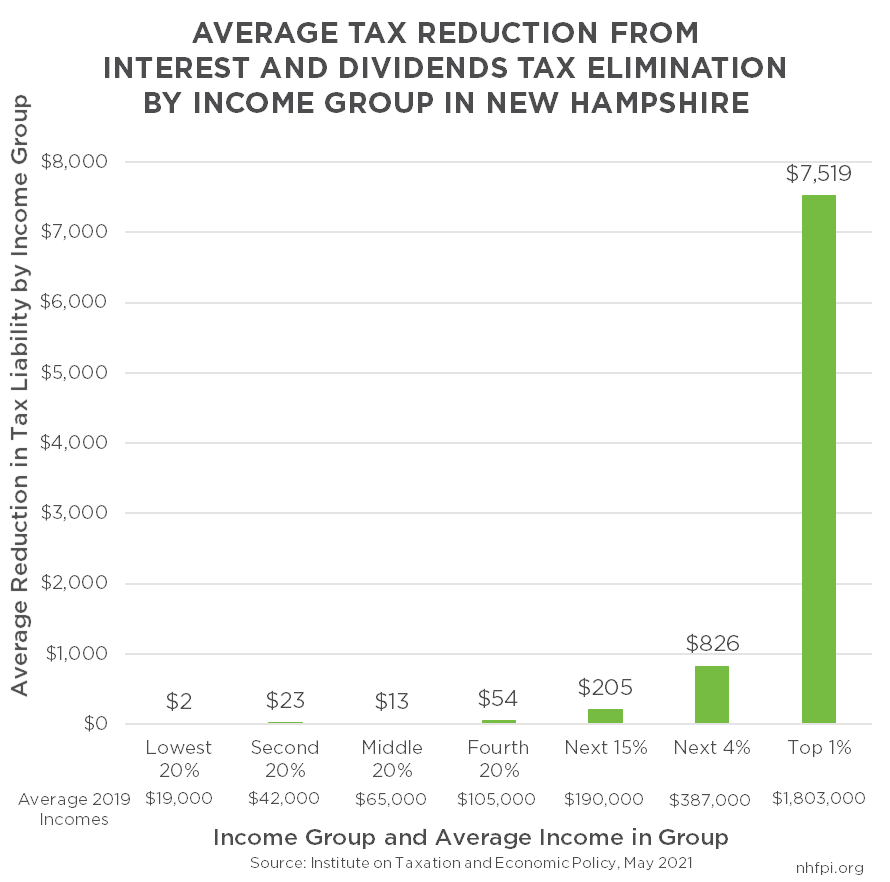

The Interest and Dividends Tax is a 5 percent tax on income earned by individuals and certain business entities from the ownership of certain assets. In SFY 2020, the Interest and Dividends Tax provided approximately 5.0 percent of all the revenue flowing to the State’s combined General and Education Trust Funds totals.[47] The new State Budget includes policy language that will phase out the Interest and Dividends Tax, beginning at the end of the budget biennium and continuing over five years, with rate reductions starting in 2023 and ending with the tax’s repeal in 2027.

The estimated total revenue lost due to this provision, using a static analysis conducted by the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, may be $368.9 million during the phaseout period through State Fiscal Year 2028, and then another $116.9 million annually thereafter.[48] The static analysis does not account for inflation or growth in the revenue base, such as positive performance in the stock market, which may make the actual revenue losses larger.

The primary beneficiaries of this tax reduction would be high-income earners. In 2018, filers with more than $200,000 in income taxable under the Interest and Dividends Tax, which does not include wage and salary income or income from capital gains, accounted for nearly half of the revenue collected by this tax revenue source. An analysis from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy shows the change in 2019 tax liability for the bottom 20 percent of Granite State income earners was an average of $2 per person, while the highest-income one percent of New Hampshire residents would see a tax reduction of $7,519 per person on average. Nearly nine out of every ten dollars in the tax reduction would flow to the top 20 percent of income earners.[49]

Meals and Rentals Tax Reduction

The single tax change with the second-largest negative revenue impact during the budget biennium is a reduction in the Meals and Rentals Tax rate. Restaurant meals are about 80 percent of the tax base for the Meals and Rentals Tax, and the balance is comprised of hotel room and car rentals.[50] The State Budget will reduce this tax rate from 9.0 percent to 8.5 percent, starting in October 2021. This change will reduce the tax paid by the customer on a $24 restaurant meal purchase by 12 cents. The Department of Revenue Administration estimates the rate change will reduce revenues to the General and Education Trust Funds by approximately $30.4 million during the biennium.

Statewide Education Property Tax

The single largest dollar value tax policy change made in the new State Budget is a one-year, $100.0 million reduction in revenue to be collected by the SWEPT in SFY 2023. As discussed in the Local Public Education section of this Issue Brief, the SWEPT is a State tax that supports the Education Trust Fund but is not collected by the State. The State requires local governments to apply this property tax in their jurisdictions, based on calculations by the Department of Revenue Administration, to raise $363.0 million statewide to support local public education and offset a certain portion of the State’s statutory obligation to fund local public education under the education funding formula. Although the State does not collect the revenue from the SWEPT, the $100.0 million reduction is the equivalent of a reduction of that size in any other State tax revenue source, as other revenue sources would have to be used to offset that reduction and fulfill the State’s obligations.

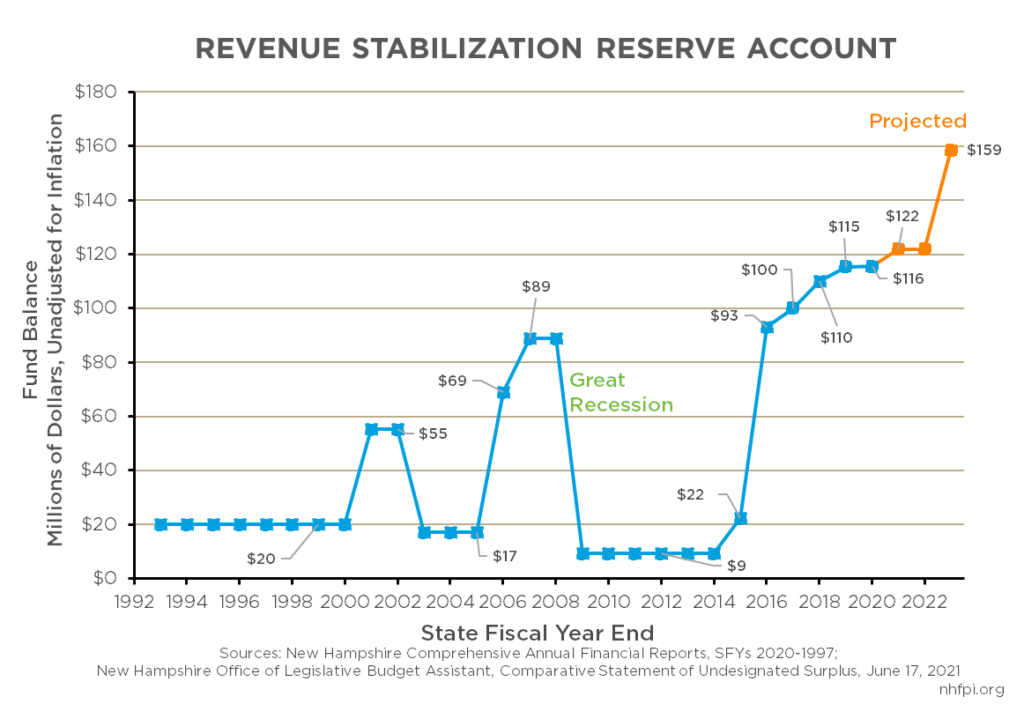

Rainy Day Fund Limit

The Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account, also known as the Rainy Day Fund, is designed in statute to fill a State Budget revenue shortfall at the end of a budget biennium. The amount that can be stored in the Rainy Day Fund from previous revenue surpluses was previously capped at 10 percent of the General Fund revenue collected in the previous year, and any additional surplus above that cap would lapse to the General Fund. State revenues collected as part of large legal settlements, of which 10 percent go to the Rainy Day Fund, are not subject to the cap. The Rainy Day Fund held $115.5 million at the end of SFY 2020, which was $46.7 million below its cap, based on SFY 2019 revenues; the cap based on SFY 2020 revenues would be lower, but still about $37.0 million above the Rainy Day Fund’s most recently audited total.[51]

The new State Budget changes the Rainy Day Fund statute to base the cap on the total revenues to the General Fund from the most recently completed biennium, which significantly increases the cap relative to prior policy, unless there are dramatic changes in revenue on a year-over-year basis. The new State Budget is also projected to increase the Rainy Day Fund balance total to $158.6 million at the end of the biennium.

Other Changes

The State Budget adds tax auditor positions at the Department of Revenue Administration. These additions are expected to add $3.9 million in General and Education Trust Fund revenue during the biennium.

A separate piece of legislation legalizes betting on historic horse races, which the Legislature projected would add $18.0 million in Education Trust Fund revenues during the biennium. These dollars were included in the Legislature’s State Budget figures.[52]