Legacy of Civil Rights chief, Ga. Congressman, lives on

Much has changed in the year since the death of US Congressman and civil rights activist John Lewis on July 17, 2020.

The nation saw the start of a mass vaccination campaign to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, which he saw only the beginning.

Previously, an unprecedented electoral cycle rocked the country, and its traditionally republican home state of Georgia sent its votes to a Democratic presidential candidate for the first time in decades.

Not long after, Georgia elected two US Democratic senators – Rev. Raphael Warnock, the first black senator in Georgian history, and a man who worked under Lewis and eventually became his mentee, Jon Ossoff.

Ossoff says he thinks of Lewis every day and often ponders how his mentor would react to the tough decisions that need to be made in the U.S. Capitol.

“Whenever I’m faced with a difficult decision, the first thing I think about is how he would lead me if I could still pick up the phone and call him as usual,” said Ossoff.

“Congressman Lewis exuded strength, kindness, and love. You could feel his deep empathy and compassion from across the room, and I think we can still feel it today, ”Ossoff said. “He was an advocate of the principles of universal human understanding and compassion, Gandh non-violence, and a civil rights titan whose personal sacrifice paved the way for the electoral law to be passed.”

More:How the Black Lives Matter Generation remembers John Lewis

Lewis’ role as a young leader in the struggle for civil rights resulted in his assuming the cloak of the older leadership of the era as he got older, and eventually becoming a congressman.

His résumé includes membership of the original 13 Freedom Riders, activists who fought against the segregated interstate system in the south in 1961. In college, he organized and participated in sit-in strikes in separate restaurants in Nashville.

He was the youngest of the “Big Six,” the leaders of six prominent civil rights organizations that helped shape the 1963 March on Washington for Work and Freedom. Lewis was president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and by age 23 he was representing the group with a speech at the historic event.

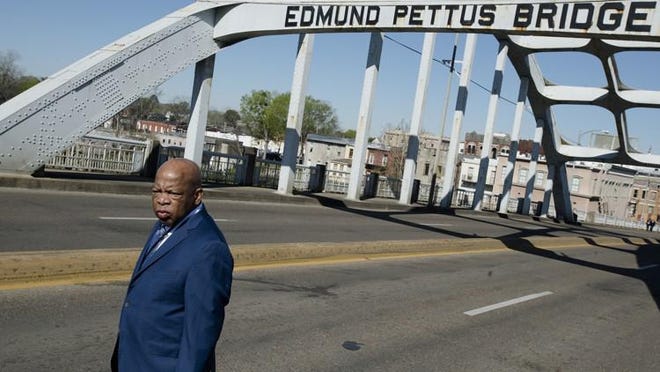

In the March in Selma, Alabama, known as Bloody Sunday in 1965, Lewis and his activist Hosea Williams led over 600 people on a march across Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they were gassed with tear gas by police.

All of these “Good Trouble”, as he famously put it, made him a permanent figure in a changing America. In 1981 he got a place on the Atlanta City Council and in 1986 a seat in Congress, establishing himself as the representative of his district.

He was re-elected to Congress 16 times and only fell below 70 percent of the vote once.

More:Georgia Senator: “Recognize the Pain of Black Savannahians and Rename Talmadge Bride”

Ossoff said Lewis’ lifelong commitment to promoting civil rights and the right to vote for black Americans and his universalist approach to governance is what he has modeled his own political career on [my] Worldview. “

“He was my mentor for almost two decades, he gave me my first job and helped me through my personal and public life,” said Ossoff. “And his commitment to universalism, to the principle that we are all human and that our universal humanity is the most important thing that unites us and should guide us, is the core of my approach to public order and public life.”

And Ossoff isn’t the only one Lewis influenced. Former Savannah Mayor Otis Johnson recalls going to Paschal’s Atlanta restaurant in the 1960s to meet with Lewis and other civil rights activists.

At the time, Johnson was a graduate student at Clark Atlanta University and a freshman to the movement. He said the atmosphere at Paschal was very down to earth, despite the large public stature of those who gathered there.

“When you hear about them in history, you tend to halo some of them. But when these guys were hanging out at Paschal’s, they were like everyone else, ”said Johnson. “And you know what it is like when the brothers get together, you have to find out what the truth is and what is not. It was like hanging out somewhere else … it was a great opportunity to just see what real leadership was like. “

Johnson said this approachable style of leadership stayed with him: keeping one foot rooted in community needs and the other rooted in the political sphere. Johnson calls it an “inside-outside strategy”.

“You have to have people inside where the guidelines and laws are made, and you have to have people outside rattling their sabers and threatening, sometimes disturbing, to get people’s attention, so they’ll be paying attention to what you’re talking about “Said Johnson.

Johnson said using this strategy eventually led Savannah to end segregation of public housing in 1963, several months before the Civil Rights Act was passed.

“We were several months ahead of what was happening at the national level, but the same strategy that worked here was being used on a much, much broader scale at the national level,” said Johnson.

But even today, in a world without John Lewis, the battle under Georgia’s controversial voting law, SB 202, continues, Johnson said.

More:Georgia Secretary of State defends new electoral law, shorter postal voting deadline

“It is so hurtful to have to cross the same area as you did in the 1960s. When we think of the Civil Rights Act of 65 that gave us the vote, and here we are in 2021 fighting to keep our voting rights. We went back 60 years man. Not only are we 60 years back, but it’s more common because much of it was originally concentrated in the south. That is now national. “

More:First Jim Crow. Now SB 202. In Georgia, voter suppression has always been a problem for black voters

Ossoff agreed, saying Lewis was proud of America, but had no illusions about the great challenges that remained.

“He was proud of all the progress America has made,” said Ossoff. “He also understood the need for eternal vigilance to protect these achievements and how much further we as a people must go to fully realize the promise of equality under the law and equal justice for all.”

Will Peebles is the corporate reporter for Savannah Morning News. He can be reached at [email protected] and @willpeeblessmn on Twitter.