How Hank Aaron made baseball a type of civil rights activism

“Martin was a huge baseball fan. We told (Aaron) not to worry, ”Young told the Atlanta Journal Constitution. “We told him he’d just keep hitting the ball. That was his job. “

ExploreHank Aaron: Hero for many, especially black people

Young said Aaron’s work on the baseball field and being the face of baseball in the deep south is a form of civil rights activism, which shows that success can be achieved when the field is the same.

It was a natural extension of Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson who confronted the breed directly with their bodies, Young said.

“He was like Joe Louis, who knocked out Max Schmeling in 38 and Jackie broke the color line in 47,” said Young. “You have to remember that Martin only started at 55. Baseball and Hank have opened many doors to many people. “

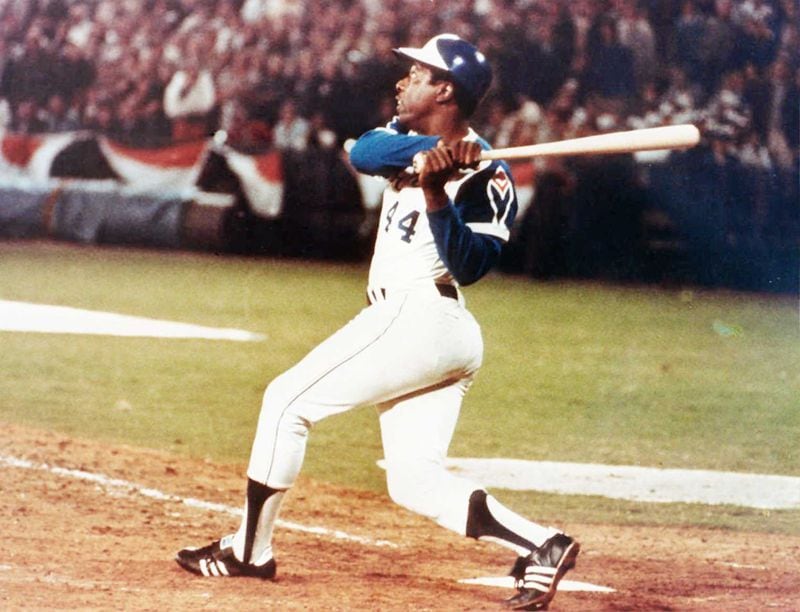

FILE – In this file photo dated April 27, 1971, Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves watches his 600th major league home game play during the third inning of a game against the San Francisco Giants. Hank Aaron, who endured racist threats with stoic dignity during his pursuit of Babe Ruth but broke the career home run record in the pre-steroid era, died early Friday, January 22, 2021. He was 86 years old. The Atlanta Braves said Aaron died peacefully in his sleep. No cause of death was given. (AP Photo / Jack Harris, File)

Photo credit: Jack Harris

Photo credit: Jack Harris

Aaron, who died Friday aged 86 in the same Atlanta home he bought when he moved, was known for his achievements in the field, as well as for his business acumen and philanthropy after his retirement.

But Aaron grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, playing baseball in a white-dominated world. While he found his voice as an outspoken critic of race and equality, he was also an eminent civil rights activist.

“Henry had never considered himself as important a historical figure as Jackie Robinson,” wrote Bryant in his 2010 Aaron biography “The Last Hero”. “And yet by integrating the South twice – first in the Sally [South Atlantic] League, and later as the first black star on the southern first major league team (no less during the apex of the civil rights movement) – his path was no less lonely in many ways and far more difficult in other ways. “

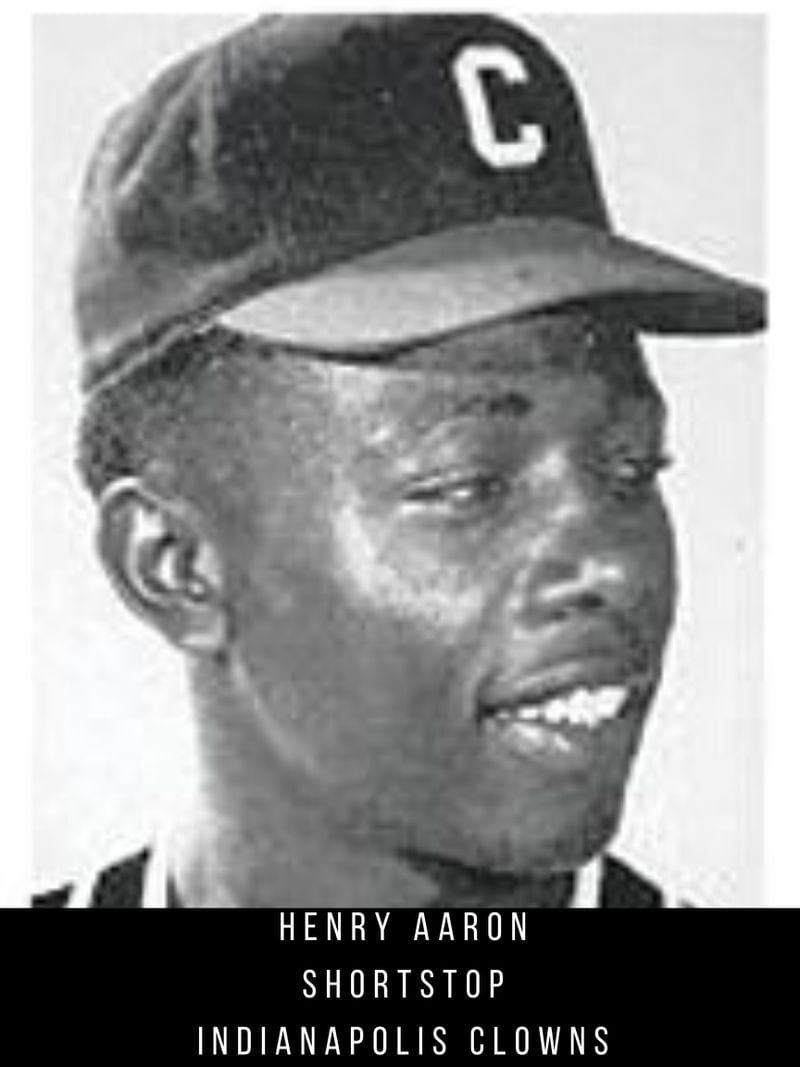

Aaron began his professional baseball career in the Negro American League in 1952 as the 18-year-old star of the Indianapolis Clowns. In 14 games, the 180-pound shortstop would hit .483 with 28 hits, six doubles, five home runs and 24 RBIs.

Hank Aaron began his career in 1952 with a Negro League team – the Indianapolis Clowns. He only played for the Clowns for three months before receiving offers from major league teams. (Negro Leagues Baseball Museum)

Photo credit: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Photo credit: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

The Boston Braves quickly signed it. Up until that point, Aaron had never shared the field with a white ball player. The team hired him to play for an integrated farm team in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

For the 1953 season, the Braves promoted him to the club Jacksonville, Florida, in the South Atlantic League. Although Robinson had just completed his sixth year with the majors for the Dodgers after breaking the color barrier, the Sally League was not yet integrated with teams in the Deep South.

Until Aaron got there.

He received a constant stream of ridicule in cities like Columbus and Macon.

In Bryant’s bio, the compliments were still backward, even when he played well enough to soften Jacksonville’s home crowd.

Felix Mantilla, a dark-skinned Puerto Rican sent to Jacksonville with Aaron, recalled a moment after the two of them helped the team win an important ball game.

As they left the ballpark, a winding fan ran up to them, smiling.

“I just wanted to say,” said the man. “That you didn’t play a damn good game.”

The $ 3 million gift from Hank and Billye Suber Aaron to the Morehouse School of Medicine will be used to expand the Hugh Gloster Medical Education building and create the Billye Suber Aaron student pavilion. The gift was given for the 40th anniversary of the school and for the call on the 31st autumn, for the white coat and for the pinning ceremony. The participating students are MSM’s largest first class class with 159 MD, MPH and PhD students. PHOTO COURTESY MOREHOUSE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Photo credit: Morehouse School of Medicine

Photo credit: Morehouse School of Medicine

After his promotion to the Milwaukee Braves in 1954, just a year before the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, Aaron began to take notice of the civil rights movement and democratic cause. While his youth idol Robinson supported Richard Nixon, Aaron traveled through Wisconsin in 1960 to promote John F. Kennedy.

But Howard wrote that even when Aaron gave his opinion on racial issues, he was always careful about being labeled a troublemaker.

“His political strategy always started behind closed doors,” wrote Howard.

ExploreBraves mourns Aaron: “We lost a legend … an incredibly great person.”

Atlanta longtime friend Xernona Clayton said while Aaron may not have been as visible as others, “He was someone we knew we could count on for contributions, or when we needed a statement or an appearance dropping off somewhere where it is important to show solidarity. ”

Upon retirement, Aaron turned his attention to business and charity, establishing programs and scholarships for black students. In 1999 he became the first black majority owner of a BMW franchise and campaigned to encourage more young black athletes to play baseball.

In 2016, Aaron and his wife, Billye Suber Aaron donated $ 3 million to the Morehouse School of Medicine as part of an expansion of the institution’s academic facilities in Atlanta. “He let people know that I was with you,” Clayton said. “He understood the pain of segregation and discrimination. He never forgot who he was and what the needs were of black people trying to achieve equality and justice. “

In 1999, Aaron, then senior vice president of the Braves, said he was “very sick and disgusted” when it was revealed that Braves aide John Rocker had made homophobic and racist comments on a Sports Illustrated profile.

“I have no place in my heart for people who feel this way,” said Aaron.

Rocker personally apologized to Aaron, who had seen his part in these attitudes late in his career.

FILE PHOTO: 730904. Hank Aarons 715th homerun on April 8, 1974.

On April 4, 1974, the opening day of his most memorable season, Aaron was restless.

He’s had 713 home runs, just two of them breaking Babe Ruth’s sacred record of 714.

The Braves opened in Cincinnati and the Reds asked him if the franchise could do something for him.

“Yes,” Aaron told them

Only six years earlier to this day, his friend Martin Luther King Jr. had been murdered.

Aaron asked that the king’s assassination be publicly acknowledged with a moment of silence before the game. In the days and months leading up to that day, Aaron had been constantly harassed by so-called fans of the baby who didn’t want a black man to break the record. Letters would come through the sack promising Aaron the same fate that King had suffered in 1968.

The moment never happened.

In the first inning, Aaron started his 714th home run and tied Ruth. Four days later, on April 8th in Atlanta, he broke the record.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who spoke to Aaron about the moment of silence before the game, said Aaron was a “hero and a champion against racial adversity.”

“He made us all proud. With his presence, he transformed baseball and helped make it a major, ”Jackson told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Friday. “He rode on people’s shoulders when we looked at him in adoration. And we rode on his shoulders as he lifted us to higher heights. “

072920 Atlanta: Andy Young (left) and Hank Aaron masked social distancing while watching the Atlanta Braves home opening game on Wednesday July 29, 2020 in Atlanta. Curtis Compton [email protected]

Photo credit: Curtis Compton

Photo credit: Curtis Compton

Eight years earlier, on a cool morning in early 1966, Young was standing outside the old American hotel on what is now Spring Street. The city held a parade to welcome the Braves to Atlanta, and Young found a seat behind “some people in country overalls because I wanted to hear and see how they would react to the black players.”

Every player on the team passed in the back seat of a convertible.

Aaron was one of the last to go through. Young listened as one of the men in overalls nudged his buddy.

“Well, if we’re going to be a big city, this guy has to be able to live anywhere he wants to live in this city,” recalled Young.

“I said, ‘You said that? ‘That must mean something. He was welcomed in this city and he loved this city. “

Staff member Shelia Poole contributed to this story.

Explore86-year-old baseball star Henry ‘Hank’ Aaron goes down in history