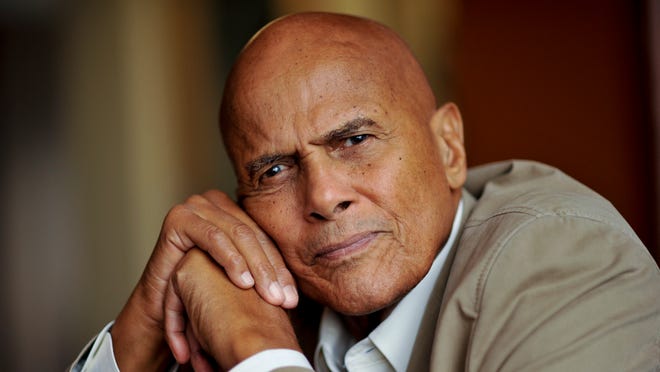

Harry Belafonte contributed to Freedom Rides, civil rights and music

Harry Belafonte never got on a greyhound bus to protest during the civil rights movement to force the US government to do what its laws promised.

Belafonte was an international star as early as the 1960s. He introduced the masses a decade earlier with calypso, a style of Afro-Caribbean music, and was the first recording artist to sell more than a million copies of an album a year.

Its growing star also lit up cinemas. He won a Tony Award for his work on Broadway and was the first Jamaican American to win an Emmy. Frank Sinatra even hired Belafonte to appear at President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration gala.

Yet Belafonte used, if not sacrificed, his early commercial success to change the way his people were treated in America.

He recruited famous friends from Hollywood to Harlem in hopes of raising funds to support civil rights and forcing the silent majority of the nation to take notice and choose a side.

Before: Harry Belafonte honored with the NAACP Spingarn Medal

A responsibility to help others

Belafonte often financed initiatives himself.

Freedom rider Bernard Lafayette recalls Belafonte’s role in mobilizing the influencers of the day. Among them was Sam Cooke, who later wrote “A Change Is Gonna Come,” one of many inspiring anthems of the time.

“When they began to identify with the movement and raise funds to help the Freedom Riders, it made a difference,” said Lafayette, who in later years became a leader of the Selma Voting Rights Movement and other civil rights campaigns.

More:The story of how the Freedom Riders revolutionized American travel and transit 60 years ago

Belafonte, a confidante of Martin Luther King Jr., financially supported the Freedom Rides, a dangerous endeavor for the participants, and an expensive campaign ranging from bail money to travel expenses to hospital bills. It marked the early years when Belafonte used his success as “King of Calypso” to support the movement.

“Ever since he stepped into the entertainment world and introduced Americans to calypso music … National Museum of African American Music in Nashville.

During this time, Belafonte hopped back and forth between two worlds as few blacks of his time did, helping one to understand the other. That included building a relationship with the Kennedy administration, said retired Professor Raymond Arsenault, a historian who has spent the past 41 years at the University of South Florida.

“He knew a lot of people, especially in the music industry,” said Arsenault, “and that’s why he became the nexus of a movement that desperately needed money to keep going.”

Top 25 protest songs:The stories behind “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and “Strange Fruit”

Music as an instrument of change

Music has always been an expression of human emotion, with a strong reference to civil rights in America.

Enslaved Africans used songs to describe their moonlit journeys to freedom, hymns like “Wade in the Water” and “Steal Away,” their authors lost in history. During the Harlem Renaissance, artists such as Langston Hughes and Billie Holiday expressed the state of the world in “I Too Sing American” and “Strange Fruit”.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Belafonte, influenced by the greats before him, giants like Paul Roberson and Holiday, tried to convince artists to speak out what they were experiencing and feeling. These efforts resulted in classics like Cooke’s biggest hit and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam”.

The path Belafonte and others have pioneered has continued over the decades, from James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and Bob Marley in the 1970s to We Are the World, a collection of the 45 greatest names in American music 1980s aiming to end the famine in Africa. In the 1990s, Public Enemy, NWA, and 2Pac exposed inequalities in black communities through hard beats and harder lyrics.

20 songs about civil rights:Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” is hopeful

Today Beyoncé, Common, Kendrick Lamar, J.Cole, HER and Lil Baby are delivering the message.

Arsenault said Belafonte’s role as fundraiser for the movement began in 1956 – the first anniversary of the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. At that time, the world became with Martin Luther King Jr.

“Back then there was a New York group called In Friendship trying to raise funds for the civil rights movement in the south,” said Arsenault, whose book Freedom Riders was largely the result of his interviews with well over 200 Freedom Riders between 1998 and 2000.

“It was there that Harry Belafonte really started his activism. He headlined a fundraising concert in New York in December 1956 and later became friends with the Kennedy family after the 1960 election.”

Belafonte’s rise to fame was not about gaining fame and fortune; It was about sending a message and setting a precedent for how black musicians should be treated.

As he grew in popularity, both his charm and intense passion for activism changed the way black entertainers were perceived in public.

In an interview with the Kansas City Star in May 1968, Belafonte noted that an artist is not one-dimensional.

“I fight (for civil rights) because I believe it can be changed. I’m fighting because I believe it should be changed, ”he said.

About this series

Sixty years ago, the first Freedom Riders set out across the south to challenge separate buses, bus stations, lunch tables, and other long-distance-related facilities. These activists were often violently confronted by police and a mob of white citizens, drawing international attention to social inequality, which became a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement. This year the USA TODAY Network examines the legacy of these trailblazers and how it affects our current moment.