Emanuel taking pictures survivor, slave dealer’s descendant take civil rights street journey collectively | Black Historical past

The minivan slips into a parking lot where a White woman hops out to hug a Black woman. Roughly the same age, they hail from opposite sides of the history they are about to confront.

For 18 months, as COVID-19 derailed their plans, the women have waited for this moment.

They shove suitcases in the trunk, buckle up side-by-side, then hit the interstate. The coming journey will take them from Charleston, the port city where about 40 percent of captive Africans arrived, to Georgia and Alabama, where many of those enslaved people toiled in bondage.

They plan to stop at key civil rights sites with a simple, yet complicated, goal: to better understand how racism became rooted so deeply that it can feel impossible to weed out.

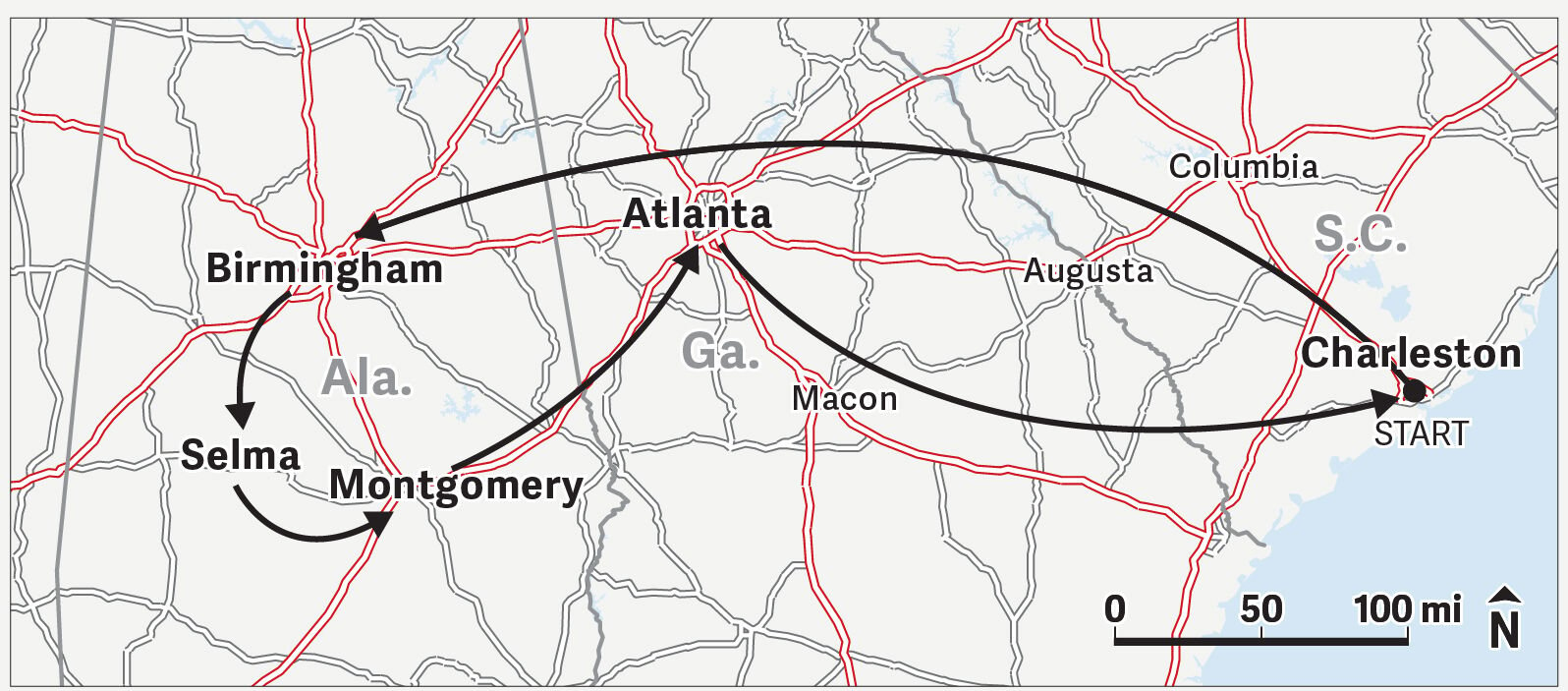

On the road for civil rights

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler traveled from Charleston to Birmingham, then to Montgomery and Selma, then Atlanta and returned to Charleston.

SOURCE: ESRI | BRANDON LOCKETT | THE POST AND COURIER

Both are native South Carolinians, both raised during segregation. But each carries that history in her own way.

Margaret Seidler, the White woman, grew up in the country club set of Charleston. She thought her family arrived after the Civil War, but recent genealogy research revealed otherwise: Her ancestors include the worst of the city’s slave traders.

Polly Sheppard, the Black woman, survived a violent eruption of modern-day racism. On June 17, six years ago almost to the day, a white supremacist sat in on Bible study at Emanuel AME Church and, after almost an hour, opened fire. He killed nine of her friends and pastors because of their race, then spared her so that she could tell the story of what he’d done.

The murderer had hoped outrage over his actions would prompt a return to segregation.

Instead, the two women met because of it.

Down South Carolina’s country roads, they head first to Montgomery, Ala. As the hours go by, and the fields of corn and soybean pass, they share stories.

Polly describes growing up in Florence, picking cotton each fall, tobacco in summers. She graduated high school in 1963 — the year 11 Black students desegregated schools in Charleston, officially making South Carolina the last state to do so.

Mugshots of Freedom Riders are part of a display at the National Center for Civil & Human Rights museum where Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard visit in Atlanta on Friday, June 11, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Florence, like most districts in the state, didn’t follow suit until 1970. Polly was well into her long nursing career by then.

Margaret attended the private, all-girl Ashley Hall — then the newly integrated Charleston High.

“All right, folks!” her husband Bob calls from the driver’s seat. “We’re in Alabama.”

Not 10 minutes later, they pass a sign for Dixie General Store, then a large Confederate flag flying atop a pole. Five smaller iterations of it follow.

Polly peers out the window.

“Look at that.”

Margaret shakes her head. “I’m sorry.”

Then and now

In Birmingham, they stay in a hotel near the 16th Street Baptist Church, where Ku Klux Klan members planted a bomb that killed four little girls one Sunday in 1963.

The church anchors an intersection with a history that still haunts America.

Four months before the bombing, the nation watched uniformed men blast children, who were protesting segregation, with high-powered fire hoses. Police dogs snapped at their young bodies.

Margaret hops from the van and faces the park where it happened. The church rises beside her as they head into the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, which opened in 2017. Polly slips in unrecognized, as she wants.

Birmingham resident Anthony Crawford delivers an unofficial tour to Polly Sheppard, Margaret Seidler and her husband Bob Seidler on Monday, June 7, 2021, in Birmingham, Ala. At Kelly Ingram Park, a statue was created to honor the four little girls killed by a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church, across the street, that was planted by Klu Klux Klan members in 1963. The park was the site of protests in Birmingham where police used firehoses and dogs on civil rights demonstrators. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

The exhibit hall greets visitors with two old water fountains. One labeled “colored” resembles a rusty urinal. The other looks clean and modern.

Margaret gestures toward them. “This is what I had growing up. Where’s our civil rights museum in Charleston?”

Nobody answers, because there isn’t one.

Around a few bends, they stop at the metal bars of a jail cell.

A month before the children marched, police arrested Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. While locked up, he wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

When Margaret and Polly read that King was arrested and jailed that day for parading without a permit, Margaret’s eyes widen.

“Justin Hunt,” she says. “Justin Hunt!”

Hunt, a 31-year-old Charleston activist, was arrested in April after protesting police brutality. His charges? Disorderly conduct — and failure to get a permit for a protest.

The two women look at each other.

“That is the same exact thing,” Margaret says.

Polly’s lips press together.

“It goes around,” she says.

As the women meander separately, Margaret arrives at an exhibit detailing a list of requests Black leaders sent White ones following police attacks on the protestors. They sought things like police sensitivity training, improved police-community relations and a citizen review board.

“This is just like …” she trails off.

She thinks about the Illumination Project, which she helped found and facilitate after the Emanuel massacre and the shooting death of Walter Scott by a White police officer in North Charleston.

Illumination Project leaders presented officials with 86 strategies for improving police-community relations. Major goals? Police training, improved police-community trust and a police-citizen advisory counsel.

Margaret joins her husband on a bench in the lobby and tears up.

“I don’t want to die and not have some kind of substantial shift,” she says.

Polly lingers, reading about John Lewis and former President Barack Obama, and then walks down a long hall toward the lobby. When she gets there, a mural of George Floyd’s face stares back at her.

She stops, a short woman before the large image.

Polly raised four sons. She cared for Black men locked up in jail. She survived a White man’s hate.

As she ducks into the gift shop, Floyd’s image lingers.

Polly Sheppard, church shooting survivor, embarked on a civil rights road trip with Margaret Seidler, who discovered slave traders among her ancestors.

Bonds of friendship

After lunch, they head to Montgomery. The women reminisce about Charleston of old, although they didn’t meet until shortly after the church shooting when Margaret spearheaded a tribute to those killed.

Just weeks later, on the exact same Sunday, they both happened to walk into Mount Zion AME Church.

Margaret, outraged by the massacre, had decided to cross the week’s most segregated hour and join a Black church. Polly arrived seeking support and a house of worship where she didn’t see the bodies of her old friends and pastors every time she went to the kitchen or restroom.

They became friends.

About six months later, Polly and fellow shooting survivor Felicia Sanders got an invite: Would they speak at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia?

Polly said no. She couldn’t possibly address such a huge crowd.

But Margaret had taught public speaking for years. She offered help. In her kitchen, she gave some advice: Plant your feet. Balance your weight. Clench your glutes.

When she got onstage, Polly planted her feet. She balanced her weight. She looked at the teleprompter.

“To heal, we must forgive,” she began.

Her voice sounded strong. She felt strong. She mentioned the shooter.

“So much hate. Too much. But as Scripture says,” she waved her glasses, “love never fails.”

“So. I. Choose. Love!” The glasses came down with each word.

“Together we can fight for that change! Together we can heal! Together we can love!”

The crowd roared.

In the van, Margaret imitates with flourish: “Together!”

The women howl with laughter.

Then Margaret remembers what courage the moment required. She leans over to whisper, “That had to be so scary.”

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard share stories along the road as they travel to Montgomery, Ala., after visiting civil rights sites in Birmingham on Tuesday, June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Marking history

The next day, they arrive at The Legacy Museum, which opened in 2018 to expose the historical pipeline from enslavement to mass incarceration. It is run by the Equal Justice Initiative, which provides legal representation to prisoners, especially those who might have been wrongly convicted.

Polly worked as a nurse at the Charleston County jail for 14 years. She cares deeply about these issues.

The trio steps inside the museum, greeted by a sign that notes: “You are standing on a site where enslaved people were warehoused.”

Nearby, a map plots slave investors’ offices around the immediate area.

It reminds them of Broad Street in Charleston, where Margaret discovered one of her ancestors ran an auction house that sold upward of 10,000 human beings. She recently got a marker put there, but laments that Charleston otherwise lacks such openness about its history.

How did Montgomery come to do so much better? Yesterday, they stopped at a sign outside EJI’s office that explains 164 slave traders operated in the city between 1848 and 1860. Many worked on the street where they stood.

Margaret’s dream is to erect these kinds of markers around Charleston. But she isn’t exactly sure how to do it.

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard look at a sculpture created by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that depicts the international and domestic slave trade at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Moving through time, from haunting holograms of enslaved people for sale, they pass postcards featuring Black people hanged in extrajudicial executions. Photographs show the mass arrests of non-violent civil rights protesters. And then, the modern era’s “war on drugs” and mass incarceration of Black men.

Polly worked at the jail during that war on drugs. It all feels very personal.

She walks to an interactive exhibit of all documented lynchings from 1877 to 1950. It’s searchable by state and county.

Charleston County shows four, all men killed in the 1919 race riot downtown. Polly is dubious that the number is only four. Her home county of Florence lists nine. In all, the museum has documented 189 across South Carolina.

A woman standing beside her begins to cry.

‘The whole truth’

That afternoon, they sit on firm black couches in EJI’s lobby. Before leaving Charleston, Bob emailed its staff letting them know Polly would be in town and would love to meet Bryan Stevenson, the lawyer of “Just Mercy” fame who is its founder and director.

Trey Walk, a friendly man with the title of “justice fellow,” greets them.

In a conference room, Bob explains their road trip. Margaret asks about all the markers in town.

Walk outlines EJI’s Community Remembrance Project, which has placed more than 40 markers at sites of racial violence.

“You need to learn the history you haven’t been taught,” he says.

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler read the names of lynching victims that are listed on hundreds of steel hanging columns marked by each county that spans dozens of states at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. The memorial was designed to create a sense of the impact of tragedy and violence of racial lynchings. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly nods. “It’s important to tell the truth.”

“The whole truth,” Margaret adds.

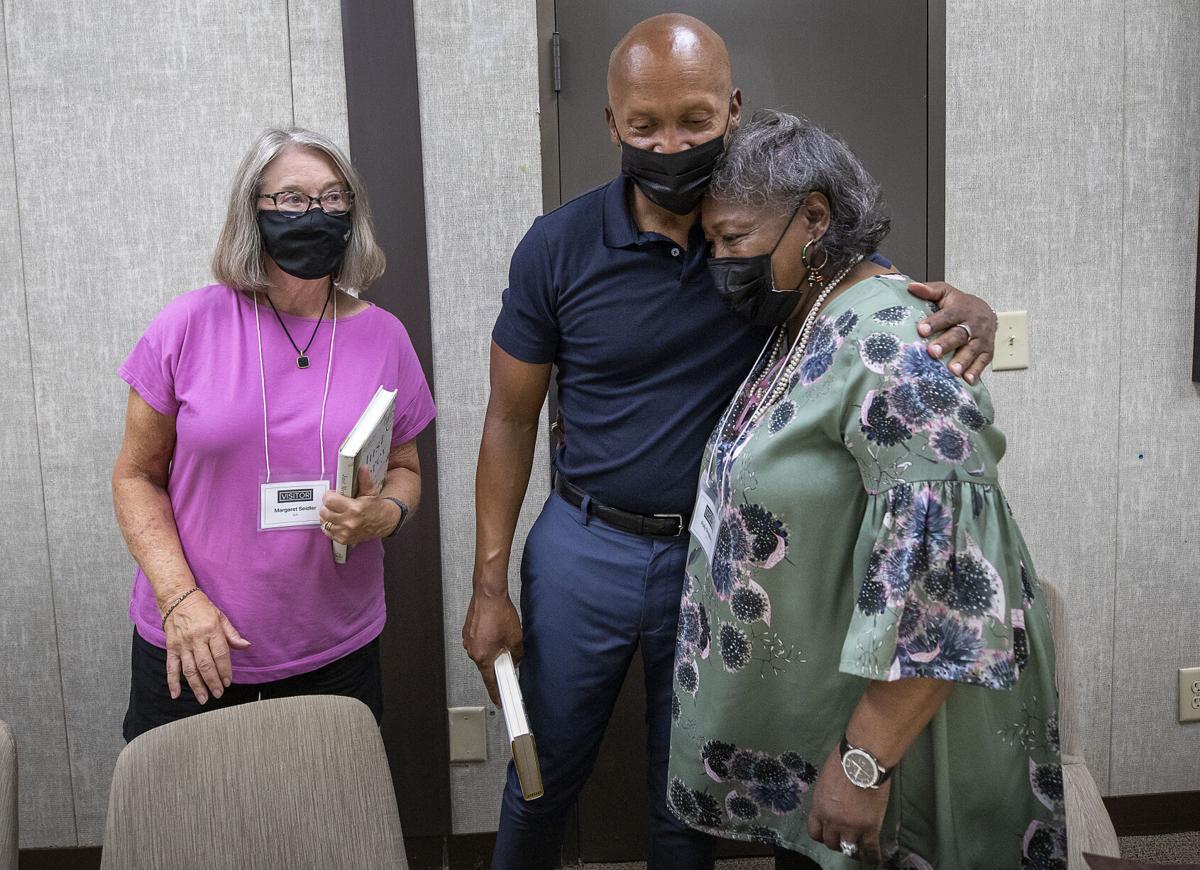

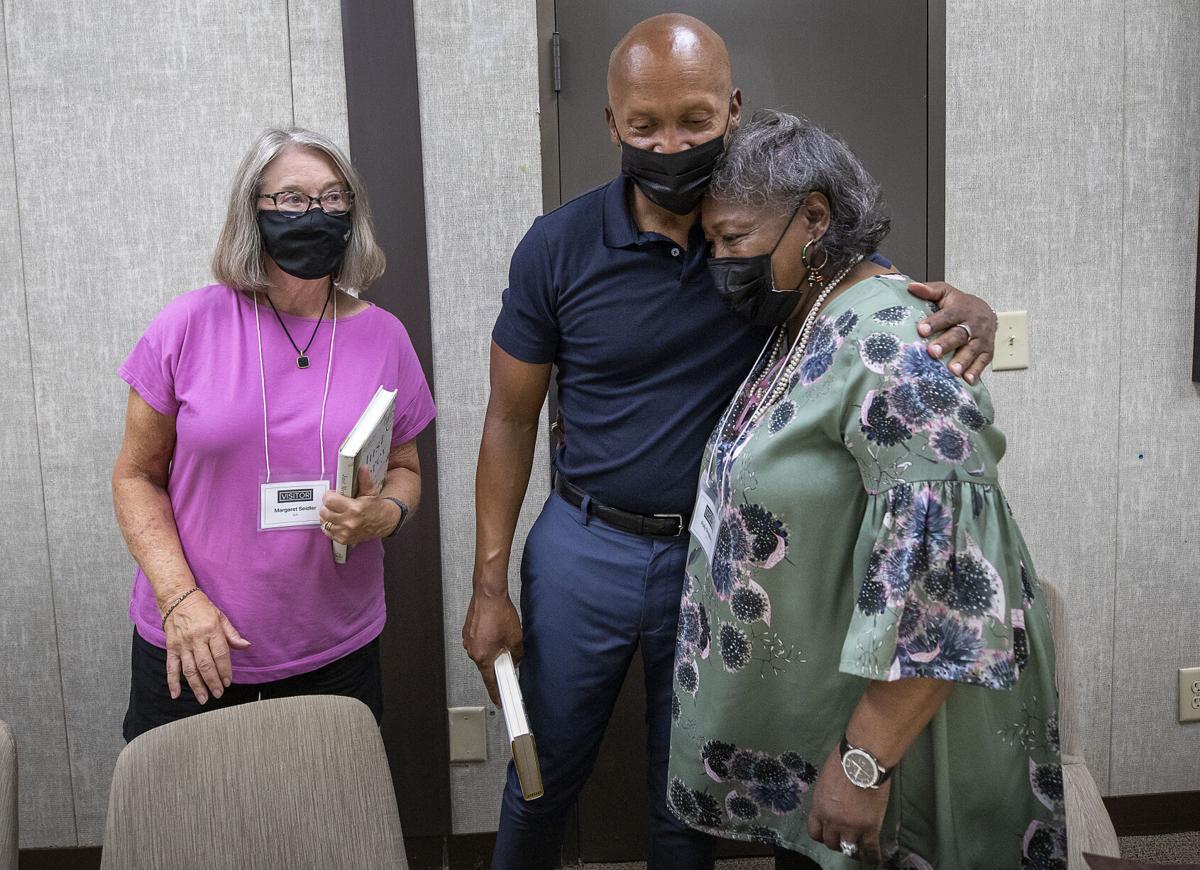

Suddenly, the conference room door opens. And there stands Stevenson, a trim man with a boyish smile.

“Hello, hello!” he says. “Thank you, thank you for coming.”

He beelines to Polly and hugs her.

“I read about you and what you’ve said and what you’ve done,” he says. “I am just so grateful for your peace and your love and your heart. It really moves me. It inspires me. We are just honored to have you here — honored.”

Margaret claps.

Polly thanks him.

They talk about the plaques around town. When he moved to Montgomery, he says, the city had 59 Confederate markers and monuments. He couldn’t find the word “slave” anywhere.

“We always tell people that we have to tell the truth,” he says. “The truth is not always comfortable. It’s not always popular. It’s not always easy. But we have to tell the truth.”

Before he leaves, Polly asks him to sign her copy of his book.

He opens the cover, and the room falls silent.

Polly Sheppard sits to rest after walking through The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

“To Polly Sheppard,

An amazing human being who has inspired me and millions of others. Thank you for your hope and your witness!”

Polly chuckles with delight. They hug again.

When the trio departs, Margaret bounds across the street toward their hotel, promising: “I’m ready to open Charleston up!”

Polly laughs. “I can see them running you out on a rail.”

Arm-in-arm, they enter their hotel.

Uneven progress

The last time Polly walked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, it was 2017, and John Lewis was there. That meant hordes of other people were, too, all walking toward a press conference at the top.

This time, she wants to cross it on her own terms.

Rain pummels the van during the hour-long drive to Selma, and it doesn’t cease when they arrive. They have brought umbrellas, but Polly is 76, and Margaret worries about her friend’s balance on the slick uphill walk.

Plus, they have checked out of their hotel. If they get soaked, a three-hour drive to Atlanta looms ahead.

Bob Seidler accompanies Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard as they cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on June 10, 2021. The Edmund Pettus Bridge was on the route of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965 where marchers, protesting voting rights, were violently beaten and stopped by police in Selma, now knows as “Bloody Sunday.” Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

They cruise across the rusty white bridge, then pull over. After travelling more than 500 miles to this apex of their journey, they all wonder: What if the rain doesn’t ease up?

Bob reads aloud a description of the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march, when troopers beat Lewis and other protestors on the bridge.

As he does, the rain lightens. It stops.

They zoom back to the bridge and park on the main street, lined with timeworn buildings, then step outside.

The bridge, named for one of Alabama’s most famous racists, rises ahead. It looks fairly small, given the enormity of what it represents. Heavy traffic barrels over its tight four lanes.

“I’m getting goosebumps,” Margaret says, “to think what this represents.”

As they trek up its thin pedestrian lane, traffic roars just feet away. A white pickup truck accelerates hard right when it reaches them. Its tires squeal beside Polly, kicking up mist and making her jump.

An older man trudges ahead of them using a cane.

“Looks like life hasn’t changed, right?” Margaret says. “He’s not walking across the bridge because he’s doing an exercise walk.”

“He’s got no transportation,” Polly says.

“No transportation. And he’s in bad health.”

They look at the decaying structures around them.

“When you don’t want to change …” Polly says.

“When you don’t want to change over time, what do you get?” Margaret asks.

“That’s right. What do you get?”

“It looks like this.”

When they reach the top, Polly peers at the sky, suddenly grateful.

“Not a drop. And look at all the clouds!”

“I’m telling you,” Margaret says, “this trip is divine.”

When they turn around to head down, a few clouds break. On one side of the bridge, ominous dark ones still loom. On the other, the sun shines.

Close

Birmingham resident Anthony Crawford delivers an unofficial tour to Polly Sheppard, Margaret Seidler and her husband Bob Seidler on Monday, June 7, 2021, in Birmingham, Ala. At Kelly Ingram Park, a statue was created to honor the four little girls killed by a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church, across the street, that was planted by Klu Klux Klan members in 1963. The park was the site of protests in Birmingham where police used firehoses and dogs on civil rights demonstrators. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Mugshots of Freedom Riders are part of a display at the National Center for Civil & Human Rights museum where Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard visit in Atlanta on Friday, June 11, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

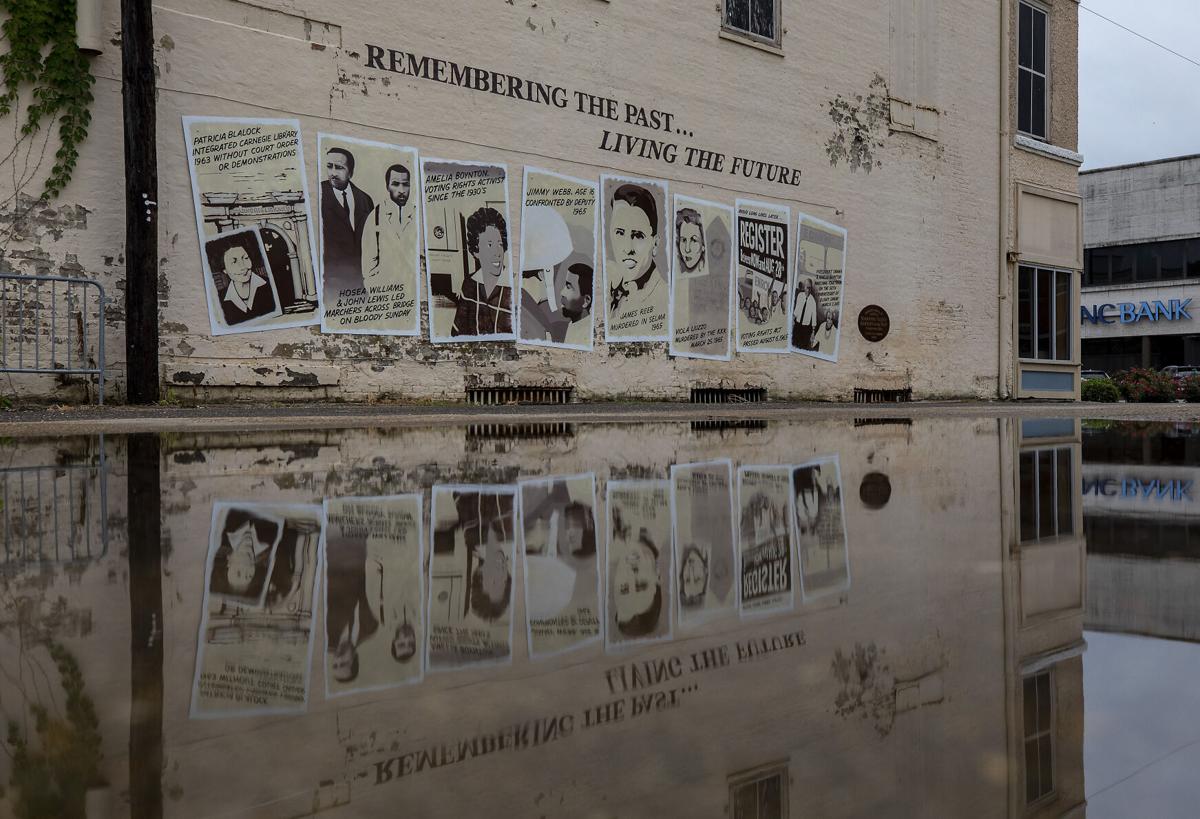

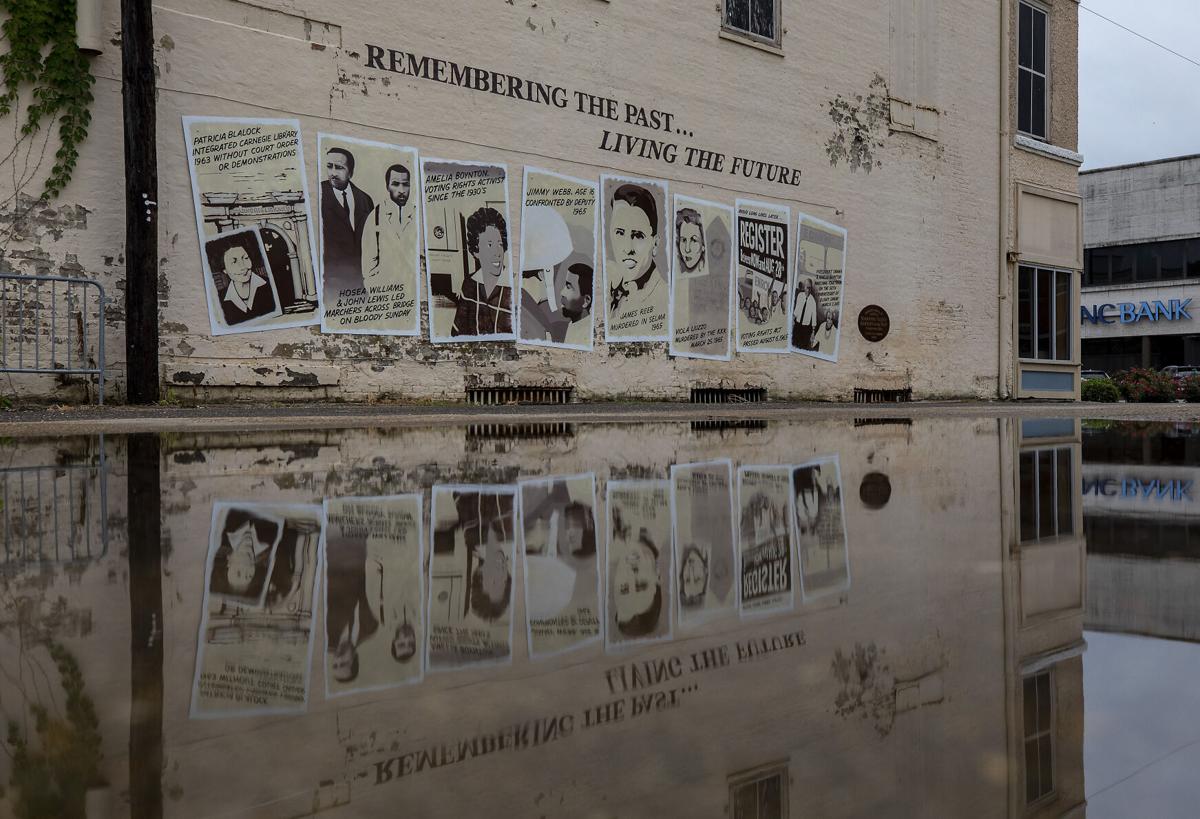

A memorial placed in March of 2020 by the Mahoning Valley Sojourn to the Past group, of Youngstown Ohio, depicts moments in the history of the Civil Rights movement in in Selma June 10, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard look at a sculpture created by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that depicts the international and domestic slave trade at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard share sides during lunch at Pannie-George’s Restaurant in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler take in the sculpture created by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that depicts the international and domestic slave trade at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard share stories along the road as they travel to Montgomery, Ala., after visiting civil rights sites in Birmingham on Tuesday, June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Two water fountains are at the entrance to the exhibit hall that welcome visitors to the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument in Birmingham, AL, Tuesday June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler read the names of lynching victims that are listed on hundreds of steel hanging columns marked by each county that spans dozens of states at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. The memorial was designed to create a sense of the impact of tragedy and violence of racial lynchings. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard sits to rest after walking through The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Names of lynching victims that are listed on hundreds of steel columns marked by each county that spans dozens of states, where the crimes took place at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

The Edmund Pettus Bridge, that was on the route of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965 where marchers, protesting voting rights, were violently beaten and stoped by police in Selma, now knows as “Bloody Sunday,” June 10, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Bob Seidler accompanies Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard as they cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on June 10, 2021. The Edmund Pettus Bridge was on the route of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965 where marchers, protesting voting rights, were violently beaten and stopped by police in Selma, now knows as “Bloody Sunday.” Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard takes her time in exhibit at the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument that pays tribute to the churches who joined the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, created and led by Fred Shuttlesworth in June 1956, in Birmingham, AL, Tuesday June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler (left) and Polly Sheppard (right) meet with Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard leave the Equal Justice Initiative after meeting with founder and Executive Director Bryan Stevenson in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Birmingham resident Anthony Crawford delivers an unofficial tour to Polly Sheppard, Margaret Seidler and her husband Bob Seidler on Monday, June 7, 2021, in Birmingham, Ala. At Kelly Ingram Park, a statue was created to honor the four little girls killed by a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church, across the street, that was planted by Klu Klux Klan members in 1963. The park was the site of protests in Birmingham where police used firehoses and dogs on civil rights demonstrators. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Mugshots of Freedom Riders are part of a display at the National Center for Civil & Human Rights museum where Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard visit in Atlanta on Friday, June 11, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

A memorial placed in March of 2020 by the Mahoning Valley Sojourn to the Past group, of Youngstown Ohio, depicts moments in the history of the Civil Rights movement in in Selma June 10, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard look at a sculpture created by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that depicts the international and domestic slave trade at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard share sides during lunch at Pannie-George’s Restaurant in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler take in the sculpture created by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that depicts the international and domestic slave trade at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard share stories along the road as they travel to Montgomery, Ala., after visiting civil rights sites in Birmingham on Tuesday, June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Two water fountains are at the entrance to the exhibit hall that welcome visitors to the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument in Birmingham, AL, Tuesday June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard and Margaret Seidler read the names of lynching victims that are listed on hundreds of steel hanging columns marked by each county that spans dozens of states at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. The memorial was designed to create a sense of the impact of tragedy and violence of racial lynchings. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard sits to rest after walking through The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., on Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Names of lynching victims that are listed on hundreds of steel columns marked by each county that spans dozens of states, where the crimes took place at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

The Edmund Pettus Bridge, that was on the route of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965 where marchers, protesting voting rights, were violently beaten and stoped by police in Selma, now knows as “Bloody Sunday,” June 10, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Bob Seidler accompanies Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard as they cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on June 10, 2021. The Edmund Pettus Bridge was on the route of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965 where marchers, protesting voting rights, were violently beaten and stopped by police in Selma, now knows as “Bloody Sunday.” Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Polly Sheppard takes her time in exhibit at the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument that pays tribute to the churches who joined the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, created and led by Fred Shuttlesworth in June 1956, in Birmingham, AL, Tuesday June 8, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler (left) and Polly Sheppard (right) meet with Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Margaret Seidler and Polly Sheppard leave the Equal Justice Initiative after meeting with founder and Executive Director Bryan Stevenson in Montgomery, AL, Wednesday June 9, 2021. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

The long road home

In Atlanta the next morning, they wait in line for the National Center for Civil and Human Rights to open.

At an exhibit, popping in headphones, the women sit side-by-side at a lunch counter. A recording plays. White people curse at them. A man threatens to stab them in the neck with a fork. Their stools vibrate, as if the furious crowd is kicking them.

The women tear up. It feels so real.

They reach an exhibit about King’s murder. Near a photograph of his body, Walter Cronkite breaks the news: “A well-dressed young White man was seen running from the scene.”

Polly’s thoughts fly to another White man fleeing the scene of murder, this one 47 years later as she frantically dialed 911.

On the long drive home, the women gossip about church friends, old friends and political figures. They have driven more than 1,000 miles together, and now both ponder what to do with their new knowledge.

“We’ve learned a lot about what we could do in Charleston,” Margaret says.

Margaret plans to contact EJI to pursue markers at key sites in Charleston.

“I’ve got to keep doing this,” she says.

“You think you can’t make a difference,” Polly says, “but if you step out, you’d be surprised.”

Polly wants a tour company to organize Black and White travelers to take trips like this one, together.

The women agree that White and Black people must learn more about their joint history. But people also must share life experiences if they want to root out racism and the de facto segregation that persists.

Juneteenth celebrations

Go to postandcourier.com/charleston_scene/ for a roundup of events celebrating Juneteeth, now a federal holiday, to remember the emancipation of enslaved people across the South.

“I just don’t know how many people would hop on a bus together and drive to Alabama,” Margaret says.

Polly thinks they would.

“Sometimes you’ve got to offer them something.”

After a while, passing fields of corn and soybean, Margaret confesses: “I thought racism was over — until Mother Emanuel.”

Polly turns and looks at her, surprised. They know so much about each other. And yet, with more than 60 years of unshared history behind them, still so little.

“You did?”