Black ministers are main rallies for voting rights simply as they did within the civil rights period

Caroline Brehman / AP

Bishop William J. Barber II speaks at the morale march on Manchin and McConnell, a poor people’s campaign rally calling for the elimination of filibuster law and the passing of the Supreme Court’s Suffrage Bill Washington, DC, 23rd June.

CNN

–

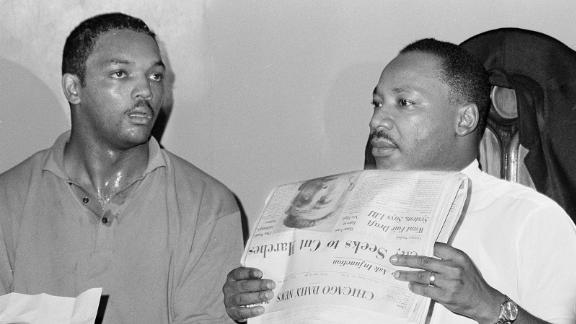

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, along with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other black religious leaders, marched in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 to seek voting rights largely encouraged by the Black Church.

Jackson was still a seminarian at the time, but said he understood that religious leaders have a “moral obligation” to fight for justice.

“Preachers stand up, people listen to them, they hear them, and they answer,” Jackson said.

Jackson still marches and rallies for the right to vote, but with a new generation of black pastors responding to a call similar to that followed by King and other ministers in the 1960s.

Larry Stoddard / AP

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., right, and his advisor, Rev. Jesse Jackson, in Chicago on August 19, 1966.

This week, some of these pastors are gathering in Washington, DC to provide the final push for Congress to pass sweeping voting laws that would counter state-level voting restrictions proposed in Texas and passed in other states. The rally will precede the 56th anniversary of the signing of the Suffrage Bill and will follow a four-day voting march through Texas led by Rev. William J. Barber II.

The events highlight the historic importance of black pastors in the struggle for the right to vote, dating back to the civil rights era, when King, Jackson and Minister Joseph Lowery were at the helm. Pastors have campaigned for equality from the pulpit, led demonstrators through neighborhoods, used their churches as resting places for demonstrators, and organized training courses for young activists. Black ministers say it is their influence that makes them central to any movement that calls for equal rights.

Barber said the church has always brought “moral awareness” to the struggle for the right to vote.

“This is a critical part of pastoral work,” said Barber, who serves as co-chair of the Campaign for the Poor. “I have to look at the people who get hurt when people steal public votes and come into office and pass public policies that harm them.”

Barber said he expected religious leaders of all races and faiths to gather in Washington, DC for the two-day rally that begins Monday. Events include a march to the Capitol, a meeting with the Texas Democrats who fled the state in July to prevent Republicans from passing election restrictions, and an evening service at Allen Chapel AME Church.

Barber said the Church also played a key role in his march in Texas last week, which featured prominent ministers including Jackson and Bishop James Dixon, president of the NAACP Houston, in its leadership. Several churches in Georgetown, Round Rock and Austin, Texas were stops on the march.

Jackson and Barber have been arrested together at least twice in the past few weeks while they were gathering in Washington, DC and Arizona for Congress to end the filibuster and pass John Lewis’ people advancement and suffrage laws. Both leaders say they will not be deterred by the police arrest and continue to advocate equal access to voting.

“I’ll keep marching until I can’t walk,” said Jackson. “We can steer society in the right direction if we can make a sacrifice for it.”

One historian said black Americans have often relied on ministers to lead social justice movements because they have the ability to bring communities together during troubled times.

Manuel Balce Ceneta / AP

Rev. Jesse Jackson, second from right, and Rev. William Barber II, second from left, stand in front of the Hart Senate Office building in Washington, DC on June 23, blocking the street.

Dr. Keisha Blain, associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh and president of the African American Intellectual History Society, said the church has historically been the zero point for faith leaders to speak out against injustice and work for civil rights groups.

“During the civil rights movement, churches were essential for organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to reach out to rural communities and inspire local activists,” Blain said. “Today’s black ministers use many of the same tactics used by religious leaders in the past.”

Dixon, who also heads the Community of Faith Church in Houston, said the Black Church is the foundation for the fight for equality. His leaders are also trusted and respected voices in the black community, he said.

Dixon pointed out King and Frederick Douglas, who were both preachers who spoke from a “biblical perspective” and heightened conversations about inequality from the political arena, he said.

King also founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, which brought together black clergy and civil rights activists who were committed to abolishing segregation and ending the disenfranchisement of black southerners with a non-violent approach. The SCLC eventually played a key role in the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

The church “was the engine,” said Dixon. “Everything we’ve done about social justice comes from the Church. There is no doubt that the most influential, formidable and inspiring institution in our community is still the Black Church. ”

Some black church leaders say they see their advocacy for the right to vote as a responsibility.

Rev. Frederick Haynes of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas marched in Texas last week and planned to travel to Washington, DC for the two-day rally. Haynes said the Bible relates to the struggle for justice for all people.

Because of this, it is always a “black belief tradition” to march, protest and be a voice for the oppressed, he said.

“Whenever there is injustice, I believe it is the responsibility of the Church people to stand up and speak up,” said Haynes. “We spent most of our trip getting this country to live up to its promises, especially when it comes to dealing with the marginalized and the most vulnerable.”