Longtime Nashville Civil Rights Activist Calls Police Officer’s Plea Deal ‘A Win For No One’ | WPLN Information

Since moving to Nashville in 1967, longtime activist Walter Searcy has seen a cycle here in Nashville: a policeman kills someone. There are calls for reform. And hardly anything changes. He hopes the plea deal doesn’t continue that pattern.Samantha MaxWPLN messages (file)

Walter Searcy has been pushing changes in the Nashville Police Department for half a century. And he’s been following the Andrew Delke case closely.

Delke resigned as a cop last week and accepted a plea deal just days before he was due to be tried. I spoke to Searcy shortly after the hearing about how little has changed in his decades of activism.

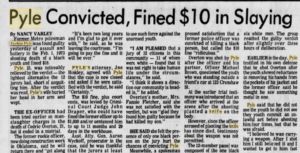

In 1973 Walter Searcy protested the shooting of another young black man by a white novice police officer. In this case, the officer was charged with manslaughter – the same crime Andrew Delke pleaded guilty to.

An excerpt from a 1970s Tennessee article about the case of Jackie Pyle, the only other Nashville police officer charged with murder for killing someone. He was eventually convicted of lesser charges and fined $ 10.Courtesy of Tennessean via Newspapers.com

This case ended in a misconduct, and the officer was eventually convicted on less serious charges. He was fined only $ 10. Like Delke, he faced the minimum sentence for his crimes.

Almost 50 years have passed and yet the result is so similar. I ask Searcy what he thinks. He chuckles on the other end of the phone line.

“Something like that. Something like that. Something like that,” he says, pausing every time he repeats it. “It just shows once more how much progress we have liked to have made, there are things that make the progress appear abnormal and that the old norms simply continue to exist. “

According to Searcy, officers are generally allowed to carry out the death penalty without charge or trial. And that those killed by the police do not get the presumption of innocence that should be guaranteed in our justice system. Officials can decide in a split second whether someone should live or die.

“And that’s a terrifying suggestion,” he says. “And that’s why so many of our parents, if not the overwhelming majority, have to give their children the instructions.”

A child holds a sign reading “When do I go from cute to dangerous” during a protest in downtown Nashville in the summer of 2020.Samantha MaxWPLN news

Searcy talks about the instructions many black children are given to avoid dangerous interactions with the police. He says parents may even warn their children not to drive at all in certain situations or times of the day, just to be safe.

“Talking about it only makes me feel more depressed,” says Searcy. Not in a clinical sense, he says. “But it annoys me. Let me say that. “

Searcy has spent more than 50 years protesting racial discrimination and police violence in Nashville. And he found it hard to see police officers being shot one by one and then acquitted of wrongdoing.

More: Learn about Searcy’s decades of efforts to improve relationships between the police and the community in episode three of WPLN’s Deadly Force podcast.

Police shot five people dead in the months leading up to the first murder trial of a Nashville police officer. These incidents are still being investigated. But the department has always defended the officers’ actions.

I ask Searcy what changes he would like to see in the training of police officers to avoid the cycle of shootings he has seen over the years.

“There is no reasonable basis for the police’s persistent misunderstandings on the street about what they are facing,” he says. “The 14-year-old who looks like a 24-year-old to the police officer.”

Searcy says that training must teach recruits to see everyone as a person first.

“If we do not lead with this, but with the demonization of the perpetrator and the other names we ascribe to criminal actors, we will continue to have these problems,” he says. “And that those responsible for training do not realize that this is only being perpetuated.”

I mention the term “implicit bias”. Many departments, including that of Nashville, have put in place training to help officers recognize the unconscious thoughts we all have about people of different races and origins. These courses have been touted as a tool to prevent police violence against black people.

But I ask Searcy if he thinks it possible for white officers to unlearn racial prejudices that even the best of intentions cannot avoid. And he says it takes more than implicit prejudice courses to solve the problem.

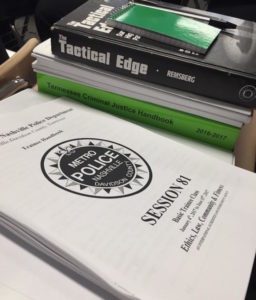

Until recently, every new recruit at the Nashville Police Academy was given a stack of reading materials on the first day of training. At the top is Tactical Edge, a textbook for high-risk patrols.Tony GonzalezWPLN

“These things happen and they are not accidental. They’re just not random, ”says Searcy. “They are a function of training. And I can remember the manual that was used late in Steve Anderson’s tenure. “

Under former boss Anderson, the book, titled Tactical Edge, remained part of the curriculum when Delke attended the academy. It taught the officers to do whatever they can to survive. And it also included dehumanizing language about people of color and public school students.

The department stopped using the book after WPLN News reported on it in 2017. An instructor at the time said he did not think the book was “controversial” but said the academy did not teach the sections identified by WPLN News.

“We supposedly got rid of the manual,” says Searcy. “But we haven’t gone far beyond these practices.”

So I ask Searcy why he thinks both sides agreed to this deal when he sees it as such a small step towards better policing. He says it would have been difficult for the prosecutor to get a conviction.

But what about Delke? I ask: do you feel that this is a victory for the defense?

“In the pantheon of things, I don’t think it’s likely to be of benefit to anyone,” says Searcy. “I mean Delke, he’s a young guy. And you know, he’s going to be a convicted felon and he’s going to be in jail for some time. So he is not what he started to be. “

Also, Searcy says the victim’s loved ones and many in the ward will not be satisfied either. With this plea deal, he says, nobody goes home without losses.

Samantha Max is the WPLN criminal justice reporter and host of the Deadly Force podcast. You can find this series and all of its reports on the case at wpln.org.

This story was produced by APM Reports as part of the Public Media Accountability Initiative, which supports investigative reporting in local media across the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

This story was produced by APM Reports as part of the Public Media Accountability Initiative, which supports investigative reporting in local media across the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.