How kids’s books stick with it the wrestle for civil rights

AMHERST – Left is a simple drawing of young Rosa McCauley, her black hair tied in a bow, posing with her parents and little brother at home in Tuskegee, Ala. To the right, pale riders in white hoods on dark horses, thundering hatred through the dark night. The question is not how these images can coexist, but why. They are pages from the children’s book by the well-known artist and activist Faith Ringgold from 1999 “If a bus could talk: The story of Rosa Parks”. (McCauley was Park’s maiden name.) And they are as powerful an emblem as any divide that still divides the heart of American society.

But in a children’s book? Do not be surprised. It’s tough stuff, but it’s in good company. Ringgold’s pages, along with more than 80 other works by 41 artists, are part of “Picture the Dream: The History of the Civil Rights Movement through Children’s Books” at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. It’s a rich, expansive genre that spans decades and is only present occasionally. Among the dozen of illustrators, aesthetics range from sharp realism to stylized fantasy. But the blunt portrayal of the stomach-twisting racial horrors of the civil rights era agrees: James Ransome’s crisp, terrifying image of black guests and their white allies being doused with cream, sugar, and mustard by vicious crowds at a separate lunch counter or ekua, Holmes ‘shady collage of Holmes’ Civil rights crusader Fannie Lou Hamer shields her head with her arms while police clubs rain.

Shadra Strickland’s illustration for “White Water: Inspired by a True Story” by Michael S. Bandy and Eric Stein.Shadra Strickland / Courtesy Candlewick Press

Children’s books are often about lessons in stories, with pictures as spoons of sugar to sweeten didactic medicine. Not here. “Picture the Dream”, curated by children’s book author Andrea Davis Pinkney, is often blatant, even harrowing. It deserves full respect for that. I have two children, ages 10 and 12. When I have learned something – an endless process with children – it is that too much protection from the ugly realities of the world only delays confrontation.

What if this confrontation never happens? Worse still, you are stuck in the buffer of the status quo, where nothing never changes. That suits a lot of people well – just look at the 2020 election, where 74 million people were happy to vote for a regressive cut – but it’s no way forward. And this is a country that needs as much progress as possible. (Throughout the show, Nate Powell’s illustrations for the graphic novel trilogy “March” were scattered across the broad arc of the civil rights movement from the perspective of John Lewis. I was so impressed that I bought all three volumes on my way out the door .)

Bryan Collier’s illustration for “All Because You Are Important” by Tami Charles.Bryan Collier / Courtesy Scholastic Inc.

Bryan Collier’s illustration for “All Because You Are Important” by Tami Charles.Bryan Collier / Courtesy Scholastic Inc.

The further development is essentially a review of what “Picture the Dream” is all about. It is divided into three chapters: “A Way Back” with illustrations from books on Jim Crow and segregation laws. (An illustration by Shadra Strickland is like a dystopian version of Norman Rockwell. It shows two little boys tapping their respective drinking fountains next to each other. It would be a little too cute, but for the “white” “and” colored “signs hanging above. ) Chapter two – the longest and for good reason – is called “The Rocks Are the Road,” and it is about the intensity of activism and protest in the 1960s. (Here you can find those pieces by Ransome and Holmes, plus a disturbingly minimal image by Benny Andrews of the 1965 standoff on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge.)

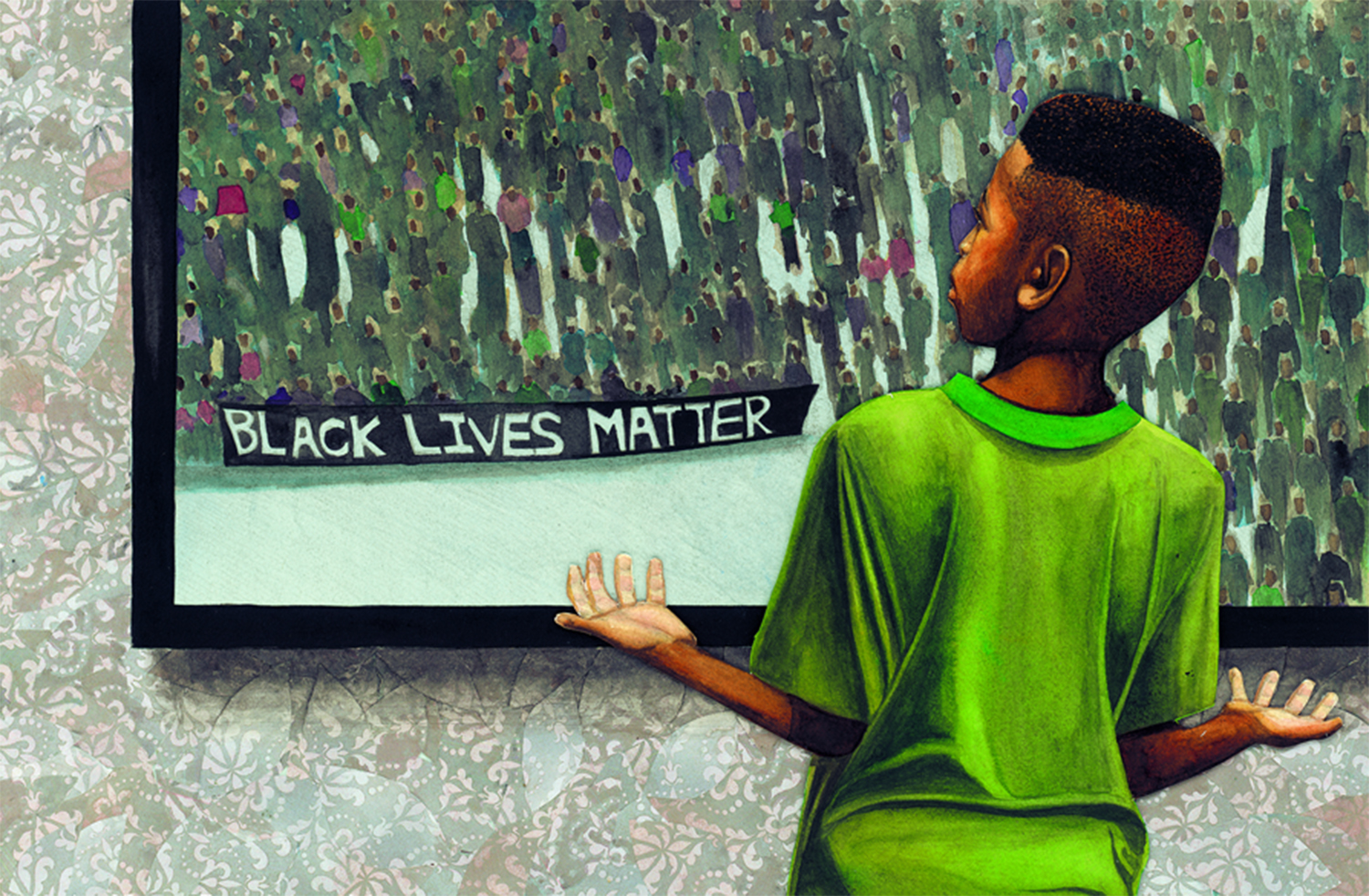

And chapter three is “Today’s Journey, Tomorrow’s Promise,” which connects past struggles with the present in all its turmoil and possibilities. A favorite for me here is Brittany Jackson’s 2019 illustration of two little girls pointing in awe at Amy Sherald’s official portrait of a beaming first lady Michelle Obama. The Black Lives Matter genre is off and on. Bryan Collier’s 2020 painting for All Because You Are Important is portrayed by a boy agogging over a photo of the crowds of demonstrators from a year ago.

Vanessa Brantley Newton’s illustration for “The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a Young Civil Rights Leader”.Vanessa Brantley Newton / Courtesy Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Vanessa Brantley Newton’s illustration for “The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a Young Civil Rights Leader”.Vanessa Brantley Newton / Courtesy Simon & Schuster, Inc.

“Picture the Dream” is a history lesson and sermon in equal parts, and in the best possible way. Heroes are always there, from Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. to Parks, Hendricks, and Ruby Bridges, who were 6 years old when she attended school in 1960 with U.S. marshals who were the first to break the color barrier of segregated schools in the south . The show teaches the now far too long lasting lesson to meet hatred and violence with nonviolence and grace in vivid picture form.

It also makes it clear that no one is exempt from the cruelty and brutality that so often accompanies the struggle for justice. It sometimes painfully reminds us that discrimination does not respect age. Emmett Till, who was murdered by white supremacists in Mississippi at the age of 14, appears twice in the works of Philippe Lardy and Tim Ladwig. Other examples include Vanessa Brantley Newton’s heartbreaking picture of Audrey Faye Hendricks, jailed at just 9 years old in the early 1960s for marching against Alabama’s segregated schools; or even more creepy: Charlotta Janssen’s collage of the KKK bombing in Birmingham in 1963, in which four little girls were killed.

You must not leave “Picture the Dream” with hope. That’s fine. Perhaps it is better that you feel differently moved. Generations galvanize early. Teach your children well and maybe the next chapter will be different. “Picture the Dream” can help.

PICTURE THE DREAM: THE STORY OF THE MOVEMENT OF CIVIL RIGHTS THROUGH CHILDREN’S BOOKS

At the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, 125 West Bay Road, Amherst. Until July 3rd. Advance booking recommended. 413-559-6300, www.carlemuseum.org

Murray Whyte can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @TheMurrayWhyte.